6.3 Cognitive Development in Childhood

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Dalia Savy

Ashley Rossi

AP Psychology 🧠

334 resourcesSee Units

Just like motor skills, cognitive skills develop in more or less fixed sequences as well. The theories of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky form the cornerstones of cognitive development theory.

Cognitive Development and Jean Piaget

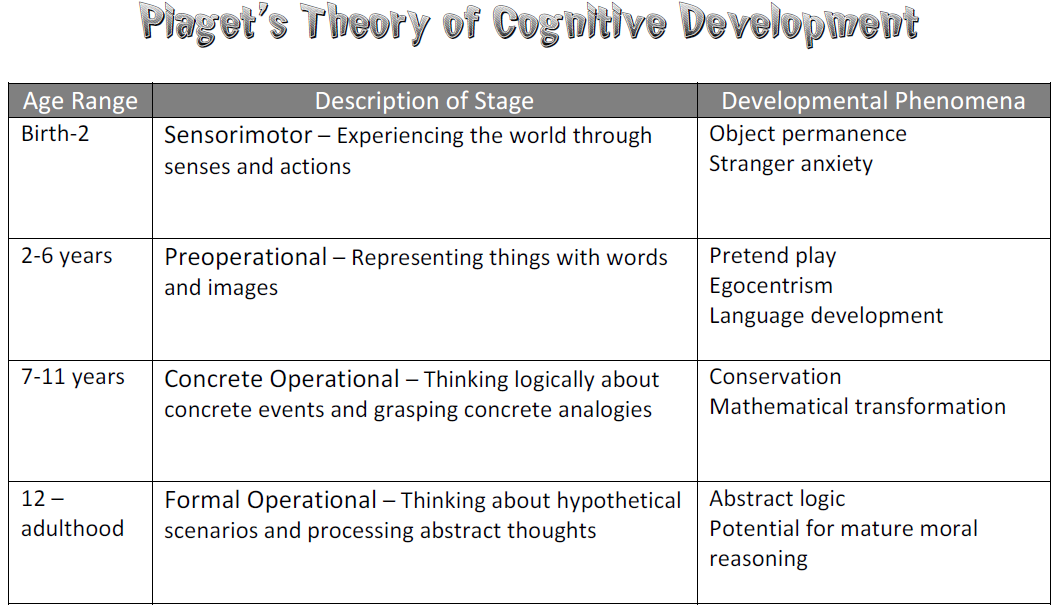

The theories of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget were, and continue to be, instrumental in understanding the cognitive development of children. Piaget isolated four stages of cognitive development and identified key developmental phenomena within each stage.

Piaget’s theory centers around the ideas of schemas, or mental frameworks. As the child develops, they rely on these schemas to make sense of new information. In fact, even as adolescents and adults, we are still heavily dependent upon our existing schemas of how the world works. 🌎

According to Piaget, children expand upon and fine-tune these schemas through the processes of assimilation and accommodation. First, children assimilate new experiences into existing schemas. Early on, a child may develop a schema for “dog” based on their exposure to the family pet 🐶

From this, they may assimilate all novel and similar stimuli into this schema (e.g. all four-legged animals). A young child may see a horse 🐴 for the first time and excitedly point to it, proclaiming it to be a “dog.”

As children interact with the world, they begin to accommodate, or adapt schemes in order to account for new information. The child will eventually learn that the schema of dog is far too broad to account for all four-legged animals and will begin to fine-tune their understanding of the animal kingdom based on this observation.

Piaget studied children for many years and concluded that cognitive development consists of four major stages.

Image Courtesy of Pinterest

Each stage corresponds with a typical age range and a general tendency towards a specific way of thinking. Throughout these stages, children mature from concrete thinking to more abstract cognitive abilities 🎨, which Piaget identified as operational thinking.

The Sensorimotor Stage

The first stage of development according to Piaget is known as the sensorimotor stage and occurs from birth until roughly two years of age. In this stage, infants readily observe the world around them and take in new information via their senses— looking, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting. As motor skills develop and the child gains control over their limbs, they can further explore the world around them.

According to Piaget, the main cognitive development in this stage is that of object permanence—the child’s ability to understand that an object exists, even if we are not consciously aware of it. Babies reach this milestone around six to eight months.

If you have ever played peek-a-boo with a newborn, you may notice that they are extremely interested in the way one seemingly appears and disappears right in front of their eyes. Similarly, if a child’s toy falls behind the couch, they may cry thinking that it is gone forever. If mom steps out of the room for a moment the infant may once again cry, believing that she too is gone forever.

Image Courtesy of Verywell Mind.

As the child matures, they are able to grasp the concept of object permanence. They understand that just because something is not within their sensory awareness does not mean it does not exist. A young child with object permanence may actually look behind the couch for their lost toy or may find solace in knowing that mom will eventually return from the next room.

Also, separation anxiety and stranger anxiety occur in this stage. The child forms close bonds with their primary caregiver(s) and may experience separation anxiety when separated from the said caregiver. Similarly, when left with an unfamiliar stranger (such as a new babysitter), the child may feel fearful and show signs of distress. Not all babies show this degree of separation and stranger anxiety, but many do.

The Preoperational Stage

The next stage of cognitive development according to Piaget is the preoperational stage. Children remain in this stage until the age of 6 or 7. In this stage, the child begins to acquire language 🗣️, but still lacks the higher-level thinking skills (such as symbolic thinking) present in adolescents and adults.

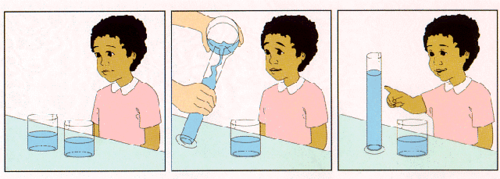

One example of higher-level mental processing can be seen through the concept of conservation. If you are asked to look at two beakers, one shallow and wide (A) and the other tall and narrow (B), you may concur that both beakers contain roughly the same amount of fluid. Sure, beaker A appears to be wider, but you are also likely to understand that beaker B is taller, which means it can account for the same amount of liquid. Before the age of 6, children may not understand this concept.

Image Courtesy of kaye_aber.

Children in this stage are also egocentric—they have difficulty understanding the views of others. A young child may stand directly in front of the TV 📺, completely unaware of the fact that they are blocking the view of others. In their mind, if they can see the TV, so can everyone else.

Despite this, children in this stage will begin to develop the theory of mind, which is a general understanding of their own and others’ mental states. They can identify if their playmate is angry and will even be able to understand what may have made them angry.

They quickly learn what kinds of behaviors please their parents and can even begin to understand what needs to occur in order to get the things that they want (i.e. the child may understand that, if they want a new toy, they will have to behave).

With this, children begin to develop empathy and skills of persuasion. They may even learn to lie, which requires them to understand what the other person wants to hear.

Alternatively, children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a disorder marked by social deficiencies, may not develop this theory of mind as seamlessly. Children with ASD tend to have more trouble understanding the emotions, desires, and reasoning of those around them. This understanding may come later as the result of more conscious attention to social cues, or it may not come at all.

Children in this stage will also favor pretend play. According to Piaget, pretend play allows children to further develop and solidify schemas. Furthermore, pretend play allows children to experiment with new scenarios. On the flip side, he found observing the pretend play of children to be a very useful tool in understanding their perception and cognitive development.

Concrete Operational Stage

Piaget’s concrete operational stage begins around age 6 or 7 and lasts until roughly 12 years of age. In this stage, children begin to grasp conservation. Similarly, they can begin to understand more complex problem-solving so long as they are given concrete materials.

If a child is asked to add 4 plus 5, they may use drawings 🖼 or markers ✒️ to complete the activity. They are not yet able to mentally (or abstractly) compute this information, but they can certainly solve it when given a concrete example. With this, operational (or abstract) thought begins to develop.

Formal Operational Stage

The final stage in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is the formal operational stage. Around age 12, reasoning expands from purely concrete to more abstract. This development of operational thought continues to unfold throughout adolescence. Children learn to infer and deduce based on their ability to reason🤔—even if these concepts are not totally concrete at first.

Sociocultural Cognitive Development and Lev Vygotsky

Unlike Piaget, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky saw cognitive development as much more fluid. Instead of occurring naturally and in fixed stages, Vygotsky theorized that cognitive development occurred gradually and is furthered by language and social interaction. Particularly, through interactions with individuals who are more skilled and cognitively advanced, children also learn the skills of more complex cognition.

Vygotsky believed that cognitive development was incumbent upon language acquisition and communication. Young children may echo their parents' words of “no!” or “bad!” when trying to resist the urge to do something they know they shouldn’t. Children who mutter to themselves while performing math problems tend to master these skills more quickly.

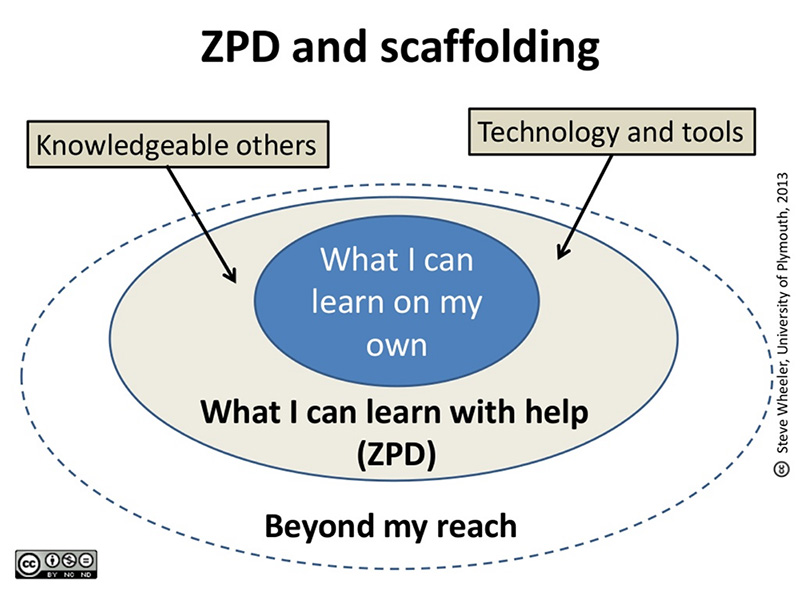

While Piaget believed that parents and teachers support a child’s natural and largely inherent cognitive development, Vygotsky reasoned that parents and teachers provide opportunities to interact with and learn from those with more skilled abilities. Vygotsky referred to these more developed mentors as more knowledgeable others.

Image Courtesy of Simply Psychology.

According to Vygotsky, children will developmentally approach readiness to learn a new skill. He referred to this as the zone of proximal development, a bridge between what the child cannot do and what they can do. In this stage, children show readiness and potential to learn a given task, but require the interaction and coaching of others to master it. 👩🏽🏫

For example, a young child may approach the zone of proximal development for walking between 9 months and one year old. They may begin to rear themselves up or rely on objects to sustain their balance. Through the aid of mom or dad holding their hands and walking with them, the child will eventually take their own first unaided steps.

Vygotsky’s theory has been especially important in the area of teaching. Through the use of scaffolding (supporting or coaching students as they work toward more complex tasks), children can develop higher-level cognitive abilities.

As a child learns to read, the parent or teacher may first read aloud to the child and incorporate new vocabulary as they go. Eventually, the more knowledgeable other may begin to ask the child to sound out words on their own or ask the child to recall what a particular word means. Over time, the task of reading is increasingly passed on from the parent/teacher to the child. 📖

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🔎Unit 1 – Scientific Foundations of Psychology

🧠Unit 2 – Biological Basis of Behavior

👀Unit 3 – Sensation & Perception

📚Unit 4 – Learning

🤔Unit 5 – Cognitive Psychology

👶🏽Unit 6 – Developmental Psychology

🤪Unit 7 – Motivation, Emotion, & Personality

🛋Unit 8 – Clinical Psychology

👫Unit 9 – Social Psychology

🗓️Previous Exam Prep

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.