Isabela Padilha

B

Brittany Schwikert

F

AP Spanish Language 🇪🇸

54 resourcesSee Units

The root of inequality is very much related to the economic system.💸 Many Latin American countries suffer from long-term inequality, which is also a result of history and socio-economic processes of the past. In this guide, we will explore the overarching economic issues of Latin America through a case study.

Economic Issues

To get to the heart of economic issues, we need to understand how political and social issues impact the allocation of resources. For efficiency, we will focus on El Salvador: the smallest country in Central America. El Salvador 🇸🇻 has long been known for its socioeconomic inequality, but in addition to longstanding inequality, it has also recently been plagued by rampant violence, unemployment, and corruption.

In this section, we will explore the large structural issues that led to the country’s current predicament. Specifically, we will review how the nation’s civil war destroyed the country’s infrastructure, leading to increased crime, unemployment, and mass migration.

The Civil War

The current political unrest in El Salvador has its roots in the nation’s violent civil war that took place from 1979-1992 (13 years long!). The civil war was between the military-led government and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), an umbrella organization of 5 leftist guerilla groups.

During the civil war, over 75,000 people died and an unknown number of people “disappeared” (e.g., kidnapped and likely murdered). During this war, El Salvador’s government gained notoriety as one of the “greatest violator human rights,” because the government was more concerned with protecting the rights of the rich, whereas the guerillas advocated for the poor through land reform and other policies.

As the guerillas attacked government strongholds, the military adopted a “drain the sea” approach, which meant that the military destroyed poor villages suspected of supporting the guerillas (with food, shelter, weapons, etc.) through bombings and massacres. The bloodiest years of the civil war were 1982 and 1983, which saw more than 8,000 civilians murdered by the government.

According to a UN Truth Commission report, more than 85 percent of the civil war atrocities (including the death of more than 75,000 people, torture campaigns, and unknown number of “disappeared” individuals) were committed by the government. Although violence between the government and the guerillas has largely subsided since the Peace Accords of 1992, political tensions and distrust between citizens and the government remains high and the public’s trust in the country’s leaders was forever altered as a result of the government’s sustained terror campaign.

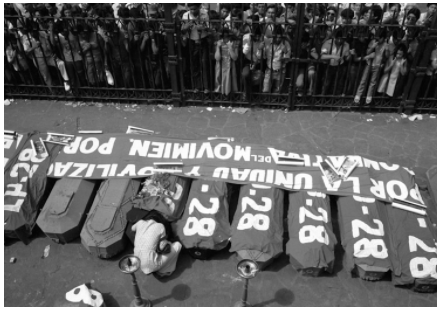

Coffins of youth killed by the National Guard after a theater performance critical of the government. Rosario Church, San Salvador. October 1979. Photo by Susan Meiselas

Economic Turmoil Sprouts Violence

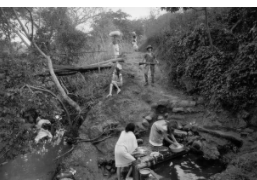

Even after the Peace Accords were finalized and ended the war in 1992, infrastructure in the country remained unchanged, and inequity between the rich and poor remains a grave issue. For example, the government failed to pass any significant legislation that would promote new buildings, roads, power plants, or water filtration systems. Rural campesinos failed to receive any access to running water or electricity for their homes. In the image below from 1991, A young FMLN guerrilla enters the village to visit family and friends where laundry is being done at communal water holes, wells, and streams.

Image by Larry Trowell, provided by Magnum Photos and The Historical Collection

The lack of infrastructure had a larger impact on rural areas because those living in rural areas had fewer opportunities for upward mobility or financial opportunities outside of their villages. However, those in the cities were not much better off due to lack of job creations from the government and limited rebuilding after the civil war.

In addition to the lack of infrastructure, El Salvador adopted the U.S. dollar as its official currency in January 2011. Adopting the U.S. dollar made life for citizens even more expensive, and basic needs like food and water became impossible to buy.

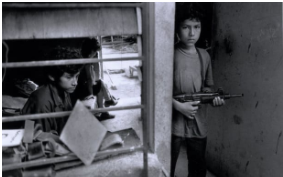

Lastly, the economic turmoil left an entire generation of young people—who had grown up in a militarized society surrounded by everyday violence—with limited opportunities. Young Salvadorans increasingly became involved with gangs, as these groups provided them with the financial opportunities and social resources that the government never chose to supply them with.

Image by Larry Trowell, provided by Magnum Photos and The Historical Collection

Increase in Crime

While the Peace Accords ended the war, it did not improve the life of Salvadorans. There was no change to the unequal economic structure between the rich and the poor, further driving a wedge between social classes.

The violent civil war created a ground zero that was ripe for recruitment of young people to drug cartels and outlying organized-crime groups. The population had no means to earn a living, and were allured by the protection and promised prosperity cartels could offer. Other outlying factors in youth violence included normalizing high school drop-outs, dysfunctional family structures, easy access to arms, alcohol, and illegal drugs, and high rates of poverty.

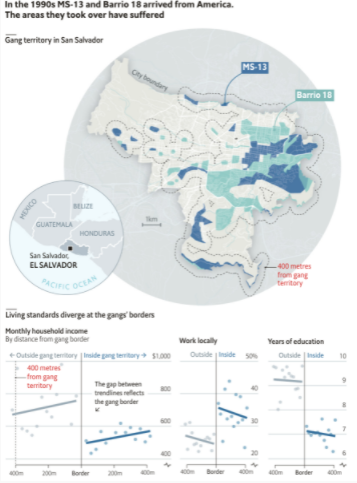

Yet another serious cause of increased crime was caused by accelerated deportations of Salvadorians from the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s. Deportees included young Salvadorans who had already formed gangs in the states, and then brought their criminal activity back to their home country. In the graphic below, you can see how two gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18, have taken over and invaded neighborhoods of the capital, San Salvador.

Mass Migration and the Lack of a Family Nucleus

With limited access to stable jobs, increasing violence, and widening inequality between classes, Salvadorans have consistently immigrated to the United States in search for a better life, or to be reunited with family members who have already immigrated. Yet that mass migration greatly impacts youth development. Those children whose parents have already fled El Salvador are at increased risk of becoming involved in youth gangs, criminal activities, or substance abuse.

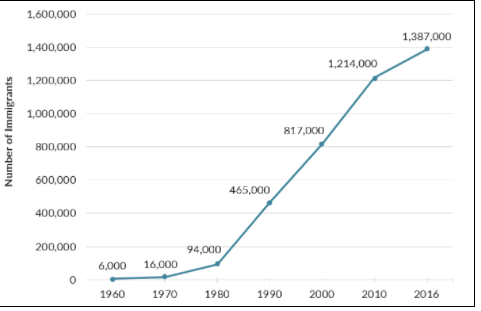

On a whole, the population of Salvadoran immigrants nearly tripled between 1990 (on the cusp of the end of the civil war) and 2016, as noted below.

Figure from Migration Policy Institute

Summary

The roots of El Salvador’s current economic unrest can be traced back to the 13-year civil war, which led to a citizenry who is severely distrustful of its government. In addition to mistrust, the government’s failure to invest in the country’s infrastructure to help bridge the rural economy with the economy in the cities severely impacted upward mobility and growth in the country, creating a perfect storm for unchecked violence and crimes. Thus, although the country’s current economic issues in isolation appear disconnected from the past, one can easily trace mass migration, unemployment, the breakdown of the family nucleus, to the 13-year civil war that disrupted the civilians faith in government.

Vocab 🔑

- Guerra civil - war between two actors/forces within a nation-state

- Desigualdad - lack of equal access to life opportunities which results in issues such as famine, poverty and social division

- Crime - Crime

- Moneda nacional - Currency of a nation

- Cartel - organizations that supply goods and want to maintain them at high level prices to debunk all competition. Usually refers to drug cartels.

- Desempleo - Unemployment

Browse Study Guides By Unit

👨👩👧Unit 1 – Families in Spanish-Speaking Countries

🗣Unit 2 – Language & Culture in Spanish-Speaking Countries

🎨Unit 3 – Beauty & Art in Spanish-Speaking Countries

🔬Unit 4 – Science & Technology in Spanish-Speaking Countries

🏠Unit 5 – Quality of Life in Spanish-Speaking Countries

💸Unit 6 – Challenges in Spanish-Speaking Countries

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.