9/11: Between History and Memory

3 min read•december 15, 2021

Eric Beckman

9/11: Between History and Memory

Next fall I will begin my thirtieth year teaching and learning history with high school students. I am now three times the age of my students. Thus, some historical topics also exist as memories for me. The Berlin Wall fell when I was student teaching my first two years in my own classroom saw the first US Gulf War and the dissolution of the Soviet. I’ve also experienced tragedies that happened in the US while with students. I arrived in my California classroom in 1995 on the morning of the terrorist attack in Oklahoma City. My first period speech and debate students and I watched televised coverage of the events. Four years and one day later, I was with speech students again, this time at a tournament in Minnesota, attempting to process the student attack on Columbine High School.

When al Qaeda terrorists attacked the US on the morning of September 11, 2001 I was teaching US History with sophomores. Unlike the aforementioned tragedies these events became the subject of ongoing class discussions in the days, weeks, and months afterwards. I have discussed them every year since then, albeit briefly in some years. On 9/11 itself my students and I experienced the event simultaneously, and this shared experience held for several years. I immediately began learning more about the attacks themselves and their context in order to supplement their memories. Over time, of course, students in my classes have had increasingly dim memories of the events of September 11. Finally, last September, one introduced me to the term 9/12 generation. She and here peers were born into a world shaped by the terrible events of 9/11.

I began considering what does it can mean to be a 9/10 educator teaching a 9/12 generation even before I learned this term. The question is especially real for me because my eldest child was born twenty four days before September 11, 2001.Although not technically a member of the 9/12 generation, she and her peers understand 9/11 as history. This is a history, however, that is associated with powerful memories for the adults in their world. Being her parent has helped me to see how high school students today see 9/11 between history and memory, even though those memories are not their own.

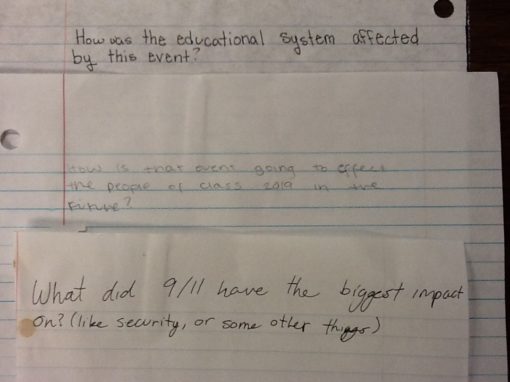

In September of 2017, when both my daughter and my World History students were juniors in high school, That fall addressed 9/11 over multiple class periods for the firs time in several years. In order to center this on the gap between history and memory, I solicited student questions. Students each wrote a question about 9/11 on a piece of paper, and I grouped them by topic for discussions during the week.

Student questions from September, 2017

In some ways these questions collapsed the distance between history and memory. Students asked many of the same things that people had on 9/11/2001. Some were and are impossible to answer fully. Others, however, have become more clear with time. Tonight I will be using the topics generated by my students to frame a discussion on 9/11 here at Fiveable. Click here to tune in live or see the replay.

On last year's anniversary educator, Iraq war veteran, and student of peace studies Scott Glew tweeted his characteristically thoughtful ideas on discussing 9/11 with students. Click on the date to see his other tweets in last year's string.

Almost two decades later, their lives are impacted by the events of that day, which didn't happen in a vacuum. Students deserve opportunities to wrestle with the complexity and discomfort that would allow them to understand this—something we as a country have yet to do.

— Scott Glew (@stglew) September 11, 2018

I hope to be able to do this tonight and going forward in my classes. The tools of historical thinking—critically sifting information, understanding our points of view, and maintaining an open mind—can be assets in this work. For students and teachers interested in this work I strongly recommend the resources curated by the 9/11 Memorial. The timelines there provide an important link between memories and history.

Fiveable

Resources

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.