Dylan Black

Jillian Holbrook

AP Chemistry 🧪

269 resourcesSee Units

The final section of Unit 7 brings together two topics: solubility and thermodynamics, which in AP Chemistry can be defined as the study of energy transfers during chemical reactions. Note that we used the word energy and not a word like “temperature” or “heat.” This is because heat is only one component of thermodynamics.

We discussed heat in Unit 6 when discussing enthalpy changes to describe a reaction as either exothermic or endothermic, meaning heat-releasing or heat-absorbing. However, there are two more thermodynamic measures that will be important for this unit and during Unit 9, which goes into much more detail about them: entropy (notated as S) and Gibbs Free Energy (notated as G). While we will wait until Unit 9 to dive deep into these concepts, in this guide, we will briefly discuss these measures and how they relate to the dissolution of soluble and sparingly soluble (what we would usually call “insoluble”) compounds.

Brief Introduction to Entropy, Gibbs Free Energy, and Thermodynamic Favorability

Before we start learning about actually dissolving substances, let’s do a quick crash course in thermodynamics so we better understand what the underlying forces of energy are when we deal with dissolution.

Entropy

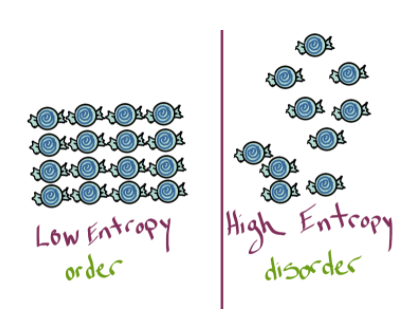

The first important concept is that of entropy. In layman’s terms, entropy describes the amount of “disorder” in a system. Entropy is also described as the number of possible arrangements in a system. Essentially, the more spread out and chaotic the system is, the higher the entropy.

We care about entropy because it describes energy flows when a system becomes more ordered. Let’s think about a less chemical example first. Suppose you have a bedroom. It is pretty easy to make your bedroom messy — rip the sheets off the bed, throw clothes on the floor, pull down posters, and go wild (sorry, parents). In this instance, you have increased your room's entropy by making it more chaotic. However, it takes a lot of energy to pick up the mess you made and return your room to a more “ordered” state. This shows the idea that systems naturally tend towards entropy, and it takes energy to keep them ordered, such as cleaning your room.

The most common chemical example of entropy changes is in melting and freezing. The melting and freezing of a substance can be described as follows (in this example we use water, but it applies to any other substance).

H2O (s) ⇌ H2O (l) ⇌ H2O (g)

We have solid water (ice) melting into liquid water and then evaporating into water vapor. In any one of these instances, entropy is increasing. In the opposite direction, entropy is decreasing. Essentially solids are the most ordered, followed by liquids, and then gases.

Gibbs Free Energy and Thermodynamic Favorability

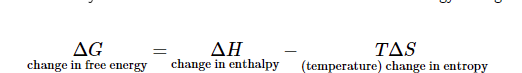

So far, we have learned about two measures of thermodynamics: enthalpy and entropy. Gibbs Free Energy combines these two values to describe the thermodynamic favorability for a reaction. The formula for Gibbs Free Energy change is as follows:

When delta G is negative, we describe the reaction as “spontaneous” or “thermodynamically favorable.” Conversely, when delta G is positive, the reaction is “nonspontaneous” or “thermodynamically unfavorable.” These words describe the relationship between enthalpy and entropy changes and how they relate to how far forward a reaction will go.

Although these concepts will be examined in greater detail in Unit 9, delta G has an intimate relationship with K, the equilibrium constant. A spontaneous reaction will have a K greater than 1 and vice versa.

Gibbs Free Energy and Dissolving Substances

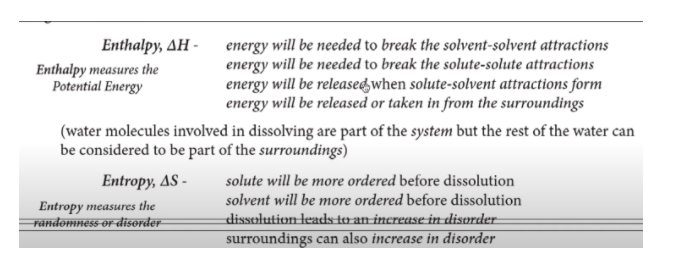

We describe enthalpy and entropy changes when dissolving in the following table:

Note that enthalpy changes refer to energy being released or absorbed to break attractions. In contrast, entropy changes refer to order or disorder.

It is important to remember that soluble and insoluble compounds exist as crystal lattices when in their solid state. Therefore, in order for a substance to dissolve, the solute-solute attractions that form the lattice must be broken down. Similarly, the intermolecular forces between the solvent, such as hydrogen bonds between water molecules, must be broken. Breaking these bonds takes energy, and forming the new attractions between ions and water molecules releases energy.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

⚛️Unit 1 – Atomic Structure & Properties

🤓Unit 2 – Molecular & Ionic Bonding

🌀Unit 3 – Intermolecular Forces & Properties

🧪Unit 4 – Chemical Reactions

👟Unit 5 – Kinetics

🔥Unit 6 – Thermodynamics

⚖️Unit 7 – Equilibrium

🍊Unit 8 – Acids & Bases

🔋Unit 9 – Applications of Thermodynamics

🧐Exam Skills

📚Study Tools

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.