Jillian Holbrook

AP European History 🇪🇺

335 resourcesSee Units

In the 18th century, the Enlightenment emerged as an intellectual and cultural movement across Europe. It was characterized by a focus on reason, science, and individualism, and it represented a shift away from traditional ways of thinking about religion, politics, and society. Enlightenment intellectuals challenged traditional beliefs and bodies of authority, including government and the church.

Political Theories

Traditional Political Theories

Thomas Hobbes

Traditional theories were supported by Enlightenment thinker Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes published his book Leviathan as a theory that humans are innately selfish and only interested in gaining wealth or power for themselves. Therefore, humans are incapable of making good choices for the good of others or participating independently in a society without strict regulations.

Image Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

Hobbes supported a traditional, authoritarian government with strict leadership that resides in one leader—a king. This style of government is representative of an absolutist monarchy, where a monarchy holds absolute power and is not guided or checked by a parliament or the people it governs.

New Political Theories

John Locke

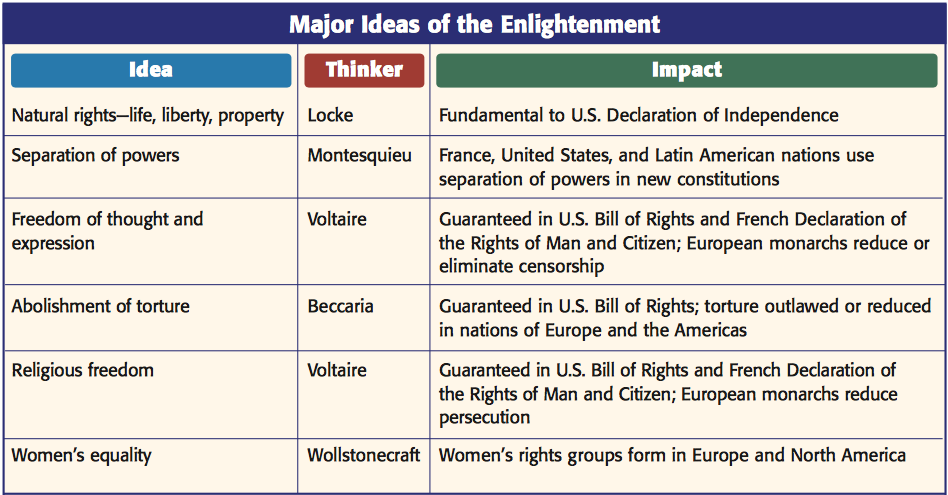

John Locke came out in opposition to Hobbes’ beliefs and popularized "tabula rasa," which is a Latin phrase meaning "blank slate." Locke argued that individuals are born without innate ideas or knowledge and that their mind is a blank slate upon which experiences and learning can be written. Essentially, all knowledge is acquired through experience, behaviors are learned from society, and people are innately good.

Additionally, Locke believed in natural rights among citizens of a nation, which center around the ideas of life, liberty, and property for all men. It is unknown how Locke felt about the rights of women specifically, but he believed that all men are given rights by God. Governments are charged with protecting natural rights, not granting them.

Other Enlightenment thinkers agreed with Locke and began writing more specific ideas in hopes of government reform. Many of these thinkers advocated for a constitutional monarchy over an absolutist monarchy.

Voltaire

Voltaire wrote Letters on the English about how the English had already formulated a Bill of Rights after the Glorious Revolution and how well it worked within their constitutional monarchy. He believed that religious tolerance should be natural and not governed.

Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote about a social contract in which everyone in society has reluctantly agreed to a function. When people are unable to or do not complete their function, society falls out of balance. He believed that men and women had certain gender roles and were unable to switch due to their innate qualities, which made them qualified for specific functions: men for work and women for raising children/homecare. Rousseau did not necessarily want this social contract. In fact, he believed that society enslaves free men, and men resorted to creating governments to protect them from society.

Baron de Montesquieu

Baron de Montesquieu was a French aristocrat who wanted to limit the role of the absolutist monarch, so he developed an idea in which governmental power is split between multiple branches that all have the ability to check the power of each other. In essence, Montesquieu proposed the concept of a system of checks and balances.

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot wanted to organize information to reach greater audiences. He included writings of several Enlightened thinkers of his time and before him, as well as scientific, historical, and philosophical information into the Encyclopedie, a one-stop-shop for information.

Women’s Rights

Women, especially in France, upheld the beliefs of the Enlightenment thinkers and helped to start and grow conversations about these beliefs in their salons and coffeehouses. However, Enlightenment thinkers did not always support the rights of women, as women were often not considered full citizens. Those who did support the equality of men and women in society, like Montesquieu, often still believed in traditional views of marriage where men dominate the household.

Others, like Rousseau, believed that women were inferior to men and did not require education to complete their societal duties of producing children and caring for the home.

Some women wrote on Enlightened thoughts and theories and published their works under the names of their husbands, and some women published their own works despite the beliefs of their male counterparts.

Early Feminism

Mary Wollstonecraft

The most famous female writer of the time was Mary Wollstonecraft wrote "A Vindication of Rights of Women" in response to Rousseau and other thinkers like him, who sought to limit the rights of women while expanding the rights of men. However, Wollstonecraft's contributions to feminist philosophy and political theory were not limited to "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman." Her literary works, such as her novels and travelogues, were also an important vehicle for her ideas about gender, society, and politics, in addition to the expression of her feminist views.

Image Courtesy of Columbia University

Wollstonecraft asserted that women were not naturally inferior to men but that their inferiority resulted from their lack of education and opportunities. She advocated for the education and empowerment of women, arguing that they should have the same rights and opportunities as men, including the right to vote and to hold property. Beyond that, Wollstonecraft also criticized the traditional gender roles and societal expectations of women, arguing that they were limiting and oppressive. She called for women to be treated as rational, autonomous individuals rather than passive and dependent beings.

Wollstonecraft's ideas were ahead of her time and met with resistance, but her work had a significant impact on the feminist movement and on the development of feminist theory.

Economic Theories

The Rise of Capitalism

Adam Smith

Like philosophists, physiocrats studied different economic practices to discover what would work best. The most well-known physiocrat was Adam Smith, who agreed with Francois Quesnay’s idea of laissez-faire economics. Laissez-faire meant an economy that is free, open, and unregulated by the government.

Adam Smith took this belief a step further with his publication of A Wealth of Nations. He combined the beliefs of many physiocrats to oppose strict government regulation of the economy. He developed the economic system of capitalism, in which the economy is regulated by supply, demand, and competition. Smith believed those three things would act as an “invisible hand” to guide pricing, products produced, workers, wages, and more.

Image Courtesy of Wikipedia

Religious Theories

Religious Tolerance

Voltaire championed freedom of choice in religion and argued vehemently against organized religion in Candide. Voltaire believed in deism, the belief that there is a God but that this entity does not act in people's daily lives according to traditional beliefs. Deism saw God more as a creator of Earth that watches how people interact in accordance with others and with science. Therefore, religion should not have an impactful role in policymaking and should not be forced upon a population. He argued for religious toleration in his Treatise on Toleration.

Religious Skepticism

Enlightened philosophes believed in skepticism, a doubt in anything one believes to know or holds true. However, some philosophes, like David Hume or Immanuel Kant, began questioning whether or not people have the ability to understand the world around them with any degree of accuracy. Skepticism threatened Christian dominance in Europe because as people continued to demand proof for their understanding, people became more adverse to simply accepting religious doctrine as fact.

Image Courtesy of Engagewithease

🎥 Watch: AP Europe - Enlightenment

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🎨Unit 1 – Renaissance & Exploration

⛪️Unit 2 – Reformation

👑Unit 3 – Absolutism & Constitutionalism

🤔Unit 4 – Scientific, Philosophical, & Political Developments

🥖Unit 5 – Conflict, Crisis, & Reaction in the Late 18th Century

🚂Unit 6 – Industrialization & Its Effects

✊Unit 7 – 19th Century Perspectives & Political Developments

💣Unit 8 – 20th Century Global Conflicts

🥶Unit 9 – Cold War & Contemporary Europe

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

👉Subject Guides

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.