Unit 7 Overview: 19th-Century Perspectives and Political Developments

4 min read•june 18, 2024

Eric Beckman

AP European History 🇪🇺

335 resourcesSee Units

Welcome to Unit 7! In this unit, we’ll focus on the period that spans from the Revolutions of 1848 to World War One. AP Euro students should look for connections to industrialization 🏭 and previous political revolutions.

📄 Study AP European History, Unit 6: Industrialization and Its Effects

Challenges to International Stability

Throughout the 19th Century, the Congress System (Unit 6) gradually broke down.

Nationalism

Nationalism, a complex idea with many types, was a big, new idea. A nation is an imagined community with many members spread out over large territories. It is imagined 💭 because most members will never meet each other. Abstract flags ⛳️ that represent large groups are a sign of nationalism.

Painting of Germania that exemplifies nationalism

Implications of Nationalism

Nationalists may define their community based on culture, politics, or perceived race. Nationalism created new states, and it broke them apart. It liberates, and it oppresses.

Cultural and racial nationalism encouraged some communities to break away from larger empires (e.g., the War of Greek Independence 🇬🇷 in Unit 6). Racial nationalism built on Darwinism to exclude and oppress people–must significantly through anti-Semitism. In response to this, some Jewish leaders developed Zionism, a form of Jewish nationalism.

National Unification

Nationalist movements both contributed to and grew from political unification 🤝 in Italy and Germany. Politicians, especially Camilo di Cavour and Otto von Bismarck, used nationalism to unite people behind their political programs to build powerful nation-states. These new states then promoted nationalism to unite their people. The new Italian and German states and the declining strength of the Ottoman Empire 🌎, caused in part by nationalism in the Balkans, upset the balance of power in Europe. This instability was a factor in World War I (Unit 8).

Map of the new German Empire

🎥 Watch: AP European History - Unification of Italy and Germany

Initially, nationalism was a tool 🛠 of liberal leaders. Later in the 19th Century, however, conservative leaders (such as Cavour, Bismarck, and Napoleon III) used popular nationalism to limit dissent and build stronger states. In Austria, nationalism challenged political stability and led to the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1867.

Modern Culture

In the second half of the 19th Century, European thought included many contradicting ideas. Objectivity and scientific realism coexisted with subjectivity and individual expression 🎨. Moreover, thinkers within these broad categories often disagreed.

Science and Society

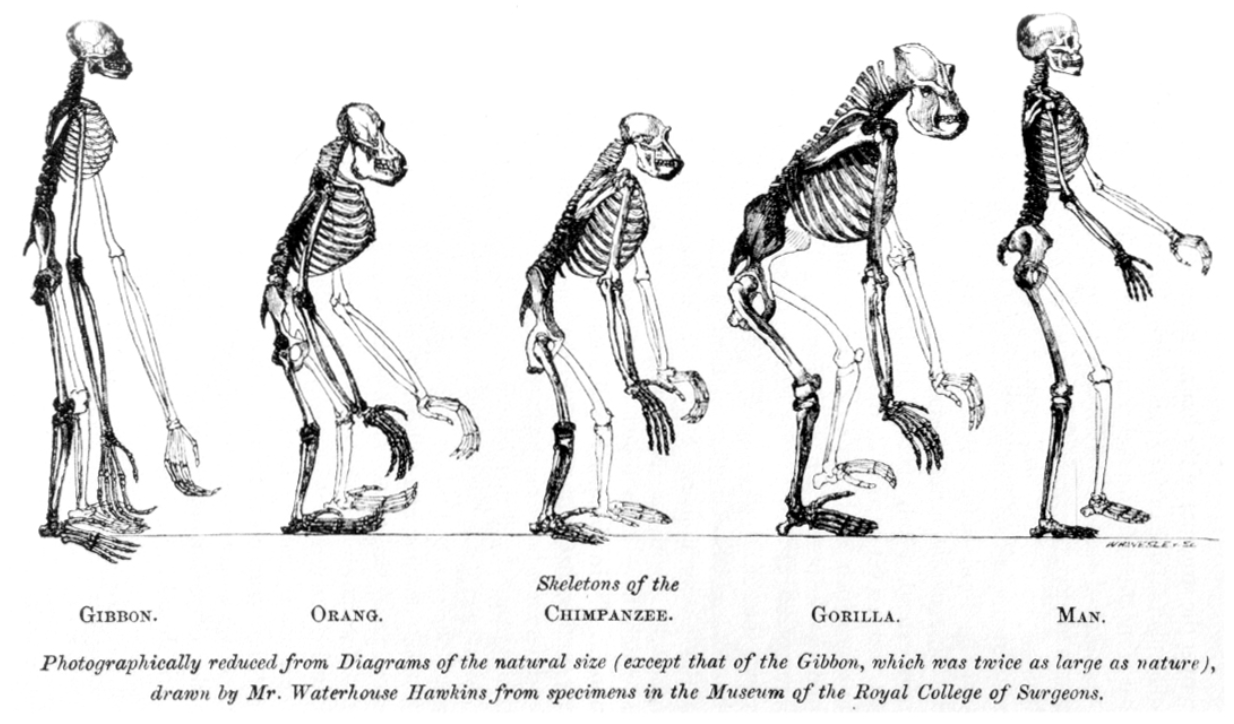

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution changed scientific and social thinking. Darwin was a biologist 🧬, but racists used his ideas. This Social Darwinism was a factor in racial nationalism and imperialism.

From Thomas Henry Huxley’s Evidence as to Man’s place in Nature, 1863

Similarly, positivist philosophers argued that science was the only path to knowledge 🧠 Positive, in this usage, means visible or known, not necessarily good. Other Europeans pushed back against positivism. In physics, the theories of Albert Einstein and others challenged the certainties of Isaac Newton’s work. Some philosophers argued that humans are irrational as a part of human nature 🌿, an idea supported by the new psychology of Sigmund Freud.

Arts and Literature

In 19th-Century European culture, Romanticism (Unit 6) dominated the first half of the century, but Realism challenged it in the second half. Realist writers ✍️ and artists aimed to accurately portray everyday life, such as the poor peasants in Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, 1857.

Later in the 19th Century, modern art challenged realism by emphasizing artists’ individual expressions. Impressionism, Post-Impression (including Henri Rousseau’s The Centenary of Independence, 1892 below), and Cubism 🧊 were all examples of modernism. This trend continued into the next century, but not everyone was a fan.

Global Empires

Powerful, industrialized states in Europe increased their global power 💪 after c. 1830. History books label this as New Imperialism because states such as Britain and Germany used new technologies and techniques on an old idea: building an empire. Chronologically, New Imperialism describes empires built after many American colonies broke free from European political control.

Aspects of the New Imperialism

Some history textbooks describe motivations for imperialism, but attentive students will notice that factors listed as such were also effects of imperialism. For instance, rivalries between states such as France and Britain were caused and resulted from claiming 🙋 colonies. Economically, industrialized countries sought raw materials and markets (people to buy their products) in colonized areas, both of which supported industrialization in Europe. Ideologically, imperialists justified their control over others by using racism influenced by Social Darwinism and claims to cultural superiority 🏆.

Technologies from the Second Industrial Revolution allowed European countries to control larger empires. Advances in weapons 🏹 gave industrialized powers military advantages, while medical advances lowered death rates for Europeans living in Africa and Asia. Communication (e.g., telegraph) and transportation (e.g., railroad 🚂) technologies facilitated control of larger territories.

British railway in East Africa, 1899

Effects of Imperialism

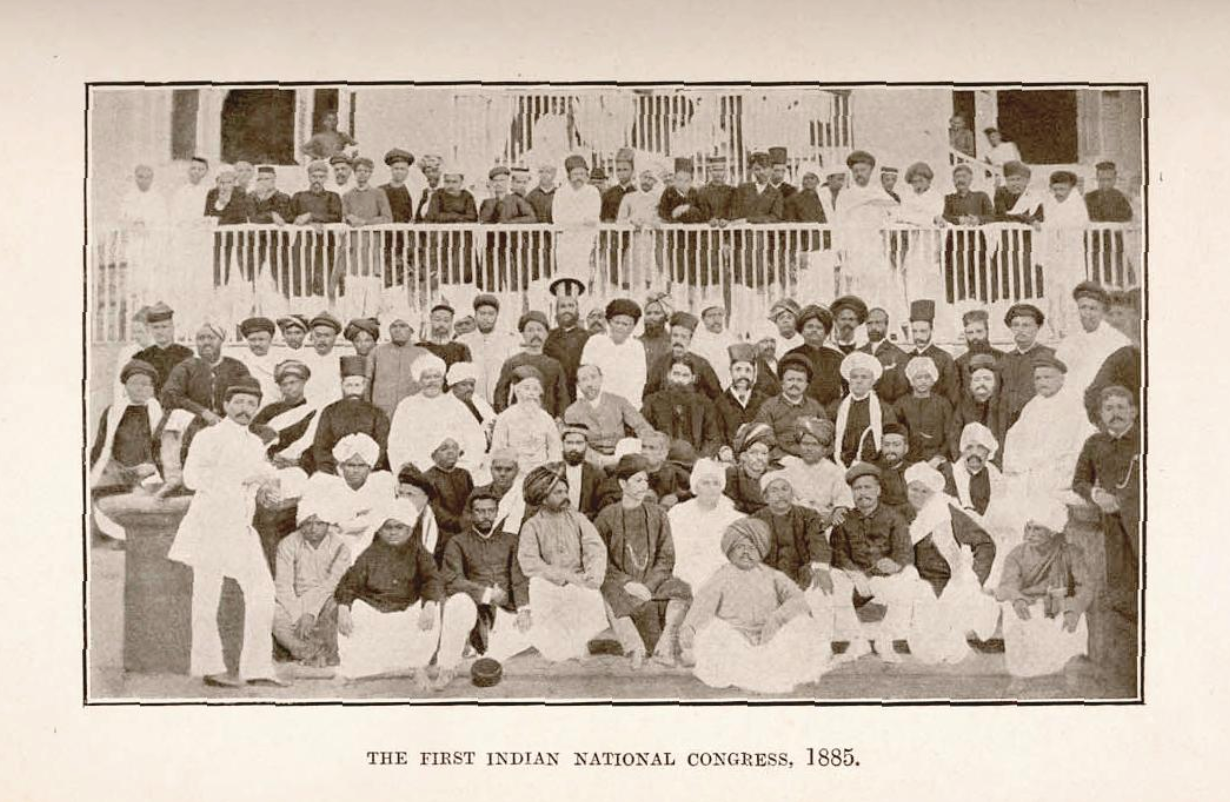

Growing global empires created tensions in Europe and around the world. Some Europeans opposed imperialism, making it a political issue. Competition for colonies overseas 🌊 was a factor in international rivalries that eventually led to World War I. Of course, non-Europeans resisted colonization of their countries. Bringing this unit full circle, nationalism was both a cause of imperialism by encouraging nation-states to expand, and a result of imperialism as colonized people organized to resist (example below).

🎥 Watch: AP European History - Nationalism, Imperialism, and Diplomatic Tensions

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🎨Unit 1 – Renaissance & Exploration

⛪️Unit 2 – Reformation

👑Unit 3 – Absolutism & Constitutionalism

🤔Unit 4 – Scientific, Philosophical, & Political Developments

🥖Unit 5 – Conflict, Crisis, & Reaction in the Late 18th Century

🚂Unit 6 – Industrialization & Its Effects

✊Unit 7 – 19th Century Perspectives & Political Developments

💣Unit 8 – 20th Century Global Conflicts

🥶Unit 9 – Cold War & Contemporary Europe

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

👉Subject Guides

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.