2.1 Minor Scales: Natural, Harmonic, and Melodic

6 min read•january 1, 2023

Mickey Hansen

AP Music Theory 🎶

72 resourcesSee Units

Three Types of Minors

The major scales we discovered in Unit 1.4 each have minor scales that is based on the notes of the major scale. The major key and minor keys with the same tonic are called parallel keys.

Just like in major scales, each minor scale has a certain pattern of whole and half steps. There are three types of minor keys: natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor.

The natural minor scale has a distinct sound that is often described as sad, serious, or melancholy. It has the pattern: whole step-half step-whole step-whole step-half step-whole step-whole step. This means that if you want the parallel natural minor given a major scale, all you have to do is flat the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees!

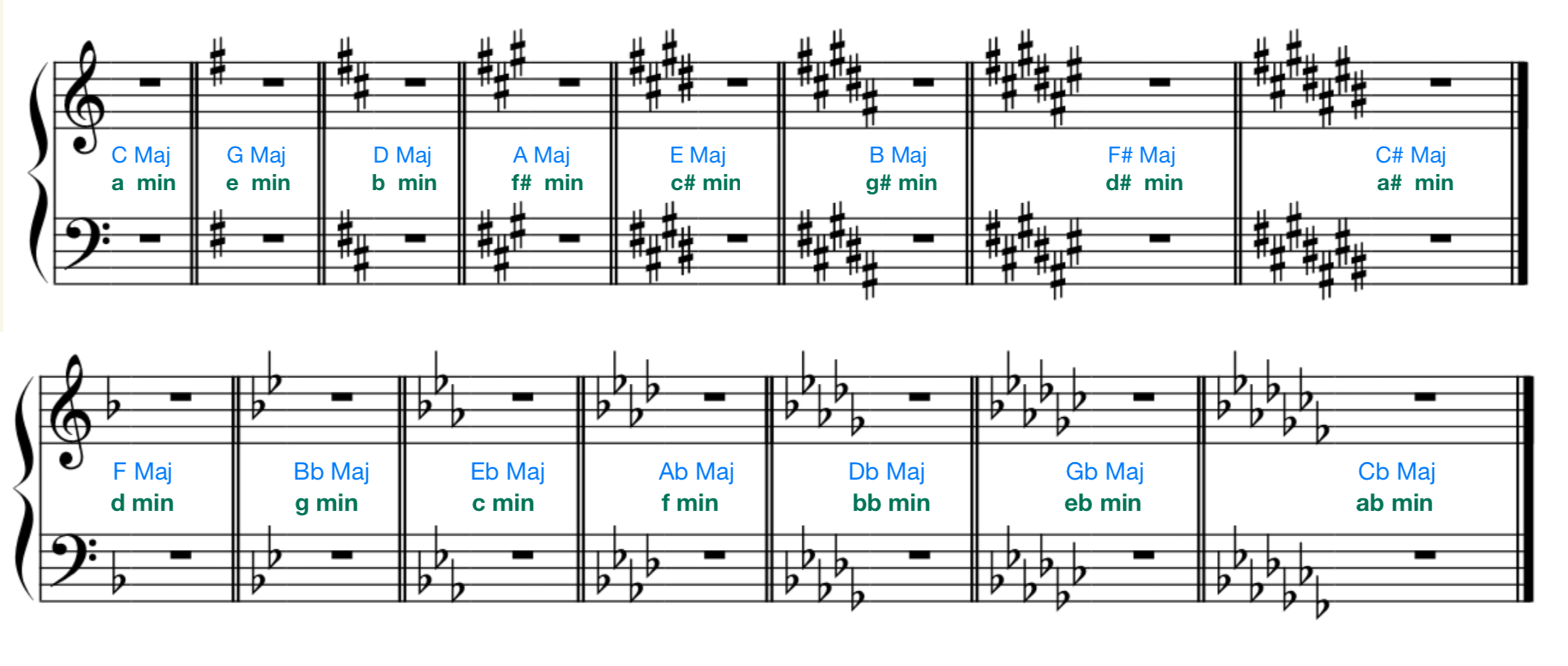

You can also build a natural minor scale by starting on the sixth degree of a major scale and using the same notes. This is called the relative minor. For example, the A natural minor scale is the same as the C major scale, starting on A:

A B C D E F G A

We say that C Major and a minor are relative keys.

Notice how C Major is capitalized, and a minor is in lowercase. That is the convention for writing about major and minor scales. Sometimes, you'll just see someone say that the piece is in the key of d, meaning that it is in d minor. However, some people will say D minor, using the word "minor" instead of the letter case to specify that the piece is in minor. We recommend being specific, especially on the AP exam, and using both lower case and the word "minor" to denote minor keys.

If you take a natural minor scale and you sharp the 7th scale degree, you get the harmonic minor scale. This is probably the minor that you're most used to hearing. We usually sharp the leading tone because our ears like to hear the half step between the seventh scale degree and the tonic - we are "led into" the tonic, giving us a good resolution to the scale.

The melodic minor scale goes one step further and sharps both the 6th and the 7th scale degrees of the natural minor scale. However, this only happens on the way up. When you play the descending melodic minor scale, it is the same as the descending natural minor scale.

Why do we have the melodic minor scale? It's called the melodic minor because it makes melodies easier to write and perform compared to the harmonic minor, which has a big jump between the flat 6 and the sharp 7. However, some music historians also believe that the melodic minor came about because the augmented 2nd harmonic minor sounded too much like the music from the Ottoman Empire at the time, which Western Europeans did not appreciate.

You won't need to know this fact for the AP exam, but I include it because it is important to recognize that our music theory that we are learning did originate from Western Europe, and many musical ideas and traditions were actively excluded from our "music theory." Outside of AP, we highly recommend that you read up on other musical theories, traditions, and scales.

When do we use the different minors?

It is important to note that we don't write in natural minor, harmonic minor, or melodic minor. For example, you won't see anyone say that this piece is in d natural minor. They just say d minor. That's because most pieces use the natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor interchangeably throughout the piece, depending on the function of each note. The key signature is always the key signature of the natural minor.

The way we come up with the relative minor given a major key is by going down three half steps from the major key. For example, A is three half steps below C, and a minor is the relative minor to C Major!

Minor Scale Degrees

It might help to consider the scale degrees of the minor scale. The minor scale has seven degrees, which are all the same as those of the major scale. As a refresher, here are their names:

- Tonic: The tonic is the first degree of the minor scale and the starting pitch. It is also the most important degree, as it gives the scale its tonality and serves as the point of resolution.

- Supertonic: The supertonic is the second degree of the minor scale. It is a major second above the tonic and is often used as a point of tension.

- Mediant: The mediant is the third degree of the minor scale. It is a minor third above the tonic and can serve as a transitional pitch between the tonic and the dominant.

- Subdominant: The subdominant is the fourth degree of the minor scale. It is a perfect fourth above the tonic and can serve as a point of stability.

- Dominant: The dominant is the fifth degree of the minor scale. It is a perfect fifth above the tonic and is the most important degree after the tonic. It serves as a point of tension and resolution.

- Submediant: The submediant is the sixth degree of the minor scale. It is a minor sixth above the tonic and can serve as a transitional pitch between the tonic and the subdominant.

- Leading tone: The leading tone is the seventh degree of the minor scale. It is a major seventh above the tonic and serves as a strong leading pitch to the tonic.

Now, notice that the leading tone here is the sharp 7th. If you didn't have a sharp 7th because you were in natural minor, you probably wouldn't refer to that note as the leading tone.

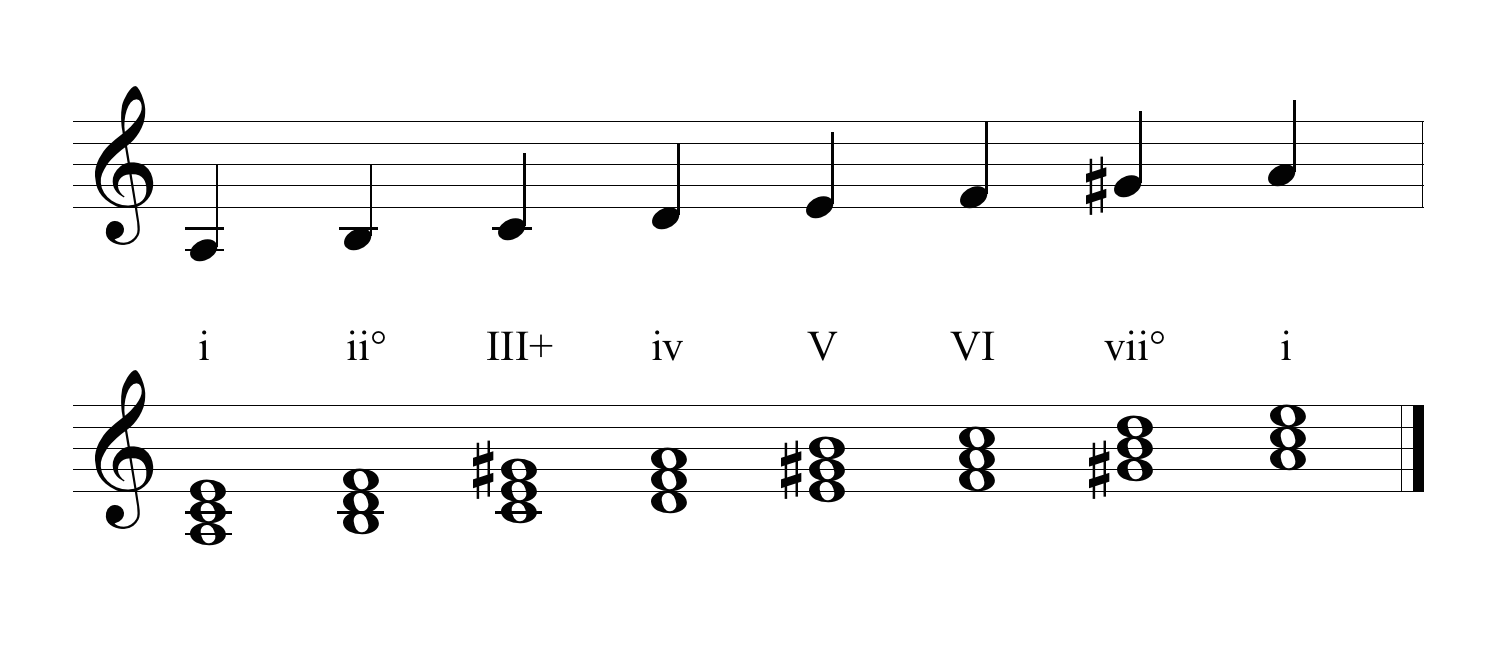

Now, let's consider building chords on these notes. The tonic i chord will be minor, because of the flat third. What about the supertonic ii chord? If the 6 is sharp, then this gives us a weird chord. In a minor, it would be B-D-F#. Sometimes, we call this half diminished. But, usually we won't sharp the 6, so we will say that it is a ii fully diminished chord.

The chord built on the third scale degree is also a little bit confusing. If the 7 is sharp, it will be an augmented chord, but if the 7 is natural, it will be a major chord. We prefer not to have augmented chords, so we will not sharp the 7 in this case, although some textbooks teach the III as augmented also.

But now, let's consider the dominant V chord. We would really like to have a V-i chord progression in our music, because it brings a strong resolution. This time, we do sharp the 7.

See how these accidentals depend on context? Here are all the chords.

Practice with Minor Scales

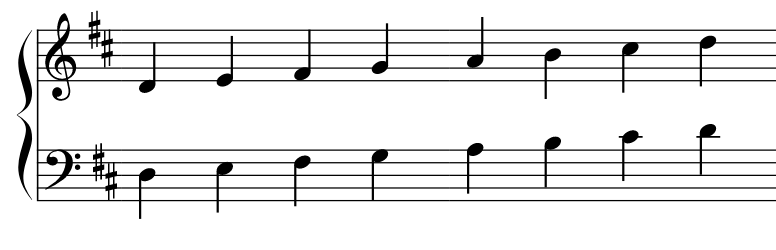

Stop scrolling! See if you can solve this problem. Here is a major scale, can you recognize which one it is? If you can, write all three of the relative minor scales.

Now, here's a step-by-step solution. First, we have to recognize what type of scale it is. We notice that in the key signature, the last sharp is C#, so the key is D Major. What about the relative minor? If we go down three half steps, we get B natural, so the relative minor is b minor.

We'll start by writing the natural minor scale, which has the same key signature as its relative major and no accidentals. We start on B, since it's b minor.

Next, for the harmonic minor, we just sharp the 7th scale degree, which is A#.

Lastly, the melodic minor will sharp the 6 and the 7 on the way up, and cancel the sharps on the way down.

Listen to an example of the melodic minor scale for b minor and another melodic minor scale!

Sight-Singing in Minor

For sight=signing in minor, I like to use the solfege. Here are the solfege names for the harmonic minor.

- Tonic: "Do"

- Supertonic: "Re"

- Mediant: "Me"

- Subdominant: "Fa"

- Dominant: "So"

- Submediant: "Le"

- Leading Tone: "Ti"

Notice that the flat third and flat sixth change to "Me" and "Le." If you were to sharp the 6, you would change Le back to La and alter the pitch. The solfege system gives you a good understanding of the relationship between the scale degrees of major keys and all the minor keys.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: Can you identify by ear what type of minor scales are below?

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🎵Unit 1 – Music Fundamentals I (Pitch, Major Scales and Key Signatures, Rhythm, Meter, and Expressive Elements)

🎶Unit 2 – Music Fundamentals II (Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture)

🎻Unit 3 – Music Fundamentals III (Triads and Seventh Chords)

🎹Unit 4 – Harmony and Voice Leading I (Chord Function, Cadence, and Phrase)

🎸Unit 5: Harmony and Voice Leading II: Chord Progressions and Predominant Function

🎤Unit 7 – Harmony and Voice Leading IV (Secondary Function)

📝Exam Skills

📆Big Reviews: Finals & Exam Prep

Fiveable

Resources

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.