Unit 4 Overview: Harmony and Voice Leading I (Chord Function, Cadence, and Phrase)

8 min read•june 18, 2024

Sumi Vora

AP Music Theory 🎶

72 resourcesSee Units

4.1: Harmony and Voice Leading I

The way individual voices of a composition move from chord to chord is called voice leading. Back in the 17th and 18th-century, when writing music was becoming normalized, rules of voice leading came about to guide composers on how to create auditorily-pleasing compositions. This era is considered the Common Practice Period (CPP), and describes the years roughly between 1650 (Baroque Period) to 1900 (Romantic Period).

Types of Motion

In four-part writing, the linear movement between two voices can happen in four different ways:

- Parallel motion: voices move in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same melodic interval.

- Similar motion: voice move in the same direction but not by the same melodic interval.

- Oblique motion: one voice remains still while the second moves up or down.

- Contrary motion: voices move in opposite directions.

18th Century Voice Leading Rules

Using the above categories, the composers of 18th-century voice leading developed guidelines for writing music in four-part harmonies:

- Voice leading should proceed mostly by step without excessive leaps.

- When possible, pitches common to adjacent chords, or common tones, should be retained in the same voice part(s).

- For clarity of voice leading, any chord should maintain soprano-alto-tenor-bass (SATB) order from high to low to avoid voice crossing.

- If a perfect fifth between two voices is not immediately repeated, it should proceed to an interval other than another perfect fifth between the same voices. This applies to parallel motion (i.e., parallel fifths) as well as contrary motion; it also applies to nonadjacent chords on successive beats.

- If a perfect octave or unison between two voices is not immediately repeated, it should proceed to an interval other than another perfect octave or perfect unison between the same voices. This applies to parallel motion (i.e., parallel octaves) as well as contrary motion; it also applies to nonadjacent chords on successive beats.

- All voices should proceed melodically with the following intervals—major and minor second, major and minor third, perfect fourth, and perfect fifth. All melodic augmented and diminished intervals should be excluded, as they produce uncharacteristic dissonances. All melodic intervals larger than a perfect fifth should also be excluded, as they create uncharacteristic disjunct motion.

- The leading tone in an outer voice (i.e., soprano or bass) should always resolve up by step to avoid an unresolved leading tone

- Outer voices may include leading tones as long as those leading tones are not doubled in another voice and resolve to the tonic by ascending in stepwise motion, to avoid an unresolved leading tone.

- All implied chords must allow the corresponding soprano notes to make harmonic sense.

- An acceptable harmonic progression can be made using tonic, supertonic, subdominant, and dominant triads exclusively, as long as the normative procedures of harmonic progression are followed.

- Repeated instances of a specific harmony— that is, repeating a particular chord in a particular position (root position or inversion)— are acceptable only if the repeated harmonies start on a strong beat. However, at the beginning of a phrase, the repeated harmonies may start on a weak beat.

- Melodic interest in a bass line may be created by balancing upward and downward motion and by balancing melodic steps and leaps.

- A bass line uses melodic leaps with greater frequency than upper voices or parts, which tend toward more stepwise motion.

- Allowable leaps include thirds, perfect fourths and fifths, sixths, and octaves, and, if resolved properly, descending diminished fifths.

- Octave leaps should be followed by changes in direction.

- The bass line may include successive leaps in the same direction as long as the pitches outline a triad.

- Repeated bass notes are acceptable only if they start on a strong beat. However, the repeated notes may start on a weak beat if it is the beginning of a phrase or if the second note is a suspension.

- Although bass lines may feature note values ranging from half notes to eighth notes, the quarter note is the most frequent rhythmic value

We also need to think about the dissonances between the outer voices. In general, you should avoid dissonances between the outer voices, which would usually occur when you are writing seventh chords. Fourths between the outer voices are okay, and generally major and minor sevenths and seconds are also okay. What you really need to watch out for are augmented and diminished intervals between the outer voices – especially the tritone.

Another thing that you should generally avoid are cross-relations, where one voice plays a note and a voice directly preceding or succeeding it plays a chromaticized version of that note. Usually, this happens in minor, when you raise the 7th. Before submitting, make sure that you don’t have a non-raised seventh near the raised seventh.

4.2: SATB Voice Leading

Musical lines, whether in instrumental or vocal pieces, may be described using the vocal parts: soprano, alto, tenor, bass. This is called SATB, for short. These are the four main vocal parts in choral music. The soprano is the highest vocal range, followed by the alto, tenor, and bass, which is the lowest vocal range. I

n choral music, these four vocal parts are typically written in four-part harmony, meaning that each part has its own unique melody that is harmonized with the other parts. The combination of these four parts creates a rich and full sound that is characteristic of choral music. In SATB (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) vocal music, voice leading refers to the way that these four vocal parts move in relation to each other. Good voice leading can help to create a smooth and harmonically interesting texture in a composition, and it is an important aspect of music composition and arranging.

When we examine a composition in four-part harmonies, we will also be using the SATB texture to complete a Roman-numeral Analysis. This means that for each chord in the harmony, we want to figure out which diatonic chord and which inversion it is in.

Doubling Rules

When you are writing a four part harmony, you will have to double (aka reuse) one note for triads, since triads only have three notes. Sometimes, you also might double the notes from a seventh chord, if you choose to exclude one note from the chord. Here is how you should pick which tone to double:

- Double the root of a triad whenever voice leading allows.

- Thirds and fifths may also be doubled in triads when they result in good voice leading.

- In all situations, always double non-tendency tones (i.e., tones other than the leading-tone and chordal seventh).

- If the fifth is omitted in a root-position seventh chord, double the root. § Following a complete root position V7, the tonic triad may have three roots and a third (no fifth).

- In 6/4 chords, always double the bass

4.3: Harmonic Progression, Functional Harmony, and Cadences

Diatonic chords usually occur in a predictable sequence called a harmonic progression that provides structure to the music. The way in which the chords are arranged in a harmonic progression can have a significant impact on the overall feel and mood of a piece of music.

The tonic is the "home key." It is the most stable chord, and as we move away from the tonic, we create tension. When we go back to the tonic, we get a sense of resolution.

Chords that have a dominant function usually immediately precede the tonic, and movement from a dominant chord to a tonic chord often creates a feeling of resolution. There are two chords that typically have a dominant function: the V and the vii.

The V chord is a stronger dominant than the vii chord because of a physics phenomenon called overtones. You won't need to know this for the AP exam, but you will need to know that scale degree 5 wants to resolve to scale degree 1, which also makes the V chord want to resolve to the I chord.

Cadences

Cadences are what come at the end of harmonic progressions. Different types of cadences provide different levels of resolution.

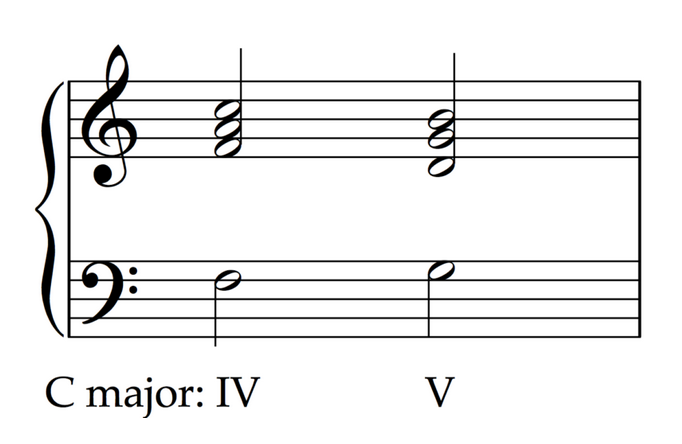

A half cadence occurs when a musical phrase ends on a V chord. Because the V chord has a dominant function, the half cadence usually feels unresolved or unfinished. Phrases that end in a half cadence sound a bit like a question, which is then answered by another phrase that ends with a stronger cadence.

A deceptive cadence has a V chord that sounds like it should resolve nicely to a I/i chord, but instead progresses to a different chord. In many cases, deceptive cadences move to a vi/VI chord or a IV/iv chord, but any non-tonic chord can end a deceptive cadence.

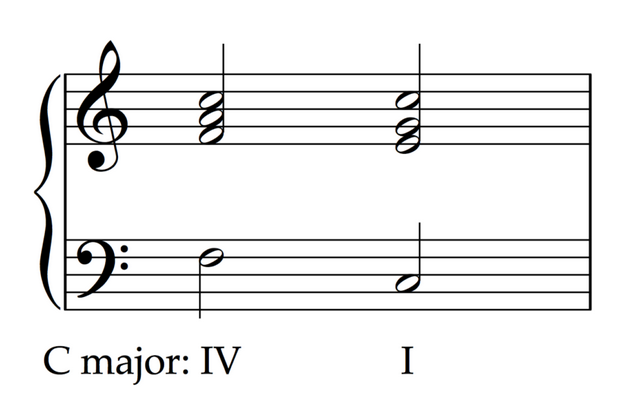

A plagal cadence (sometimes also called an "amen" cadence, since it is common in hymns) moves from the IV/iv chord to the tonic I chord. Although there is no dominant chord, plagal cadences are usually considered pretty strong resolutions.

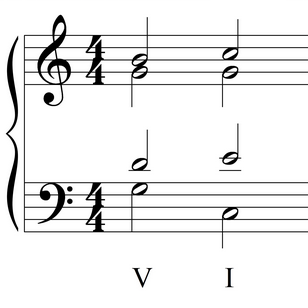

The authentic cadence comes in two forms: the perfect authentic cadence (PAC) and the imperfect authentic cadence (IAC). Both involve the dominant V chord (or dominant-functioning chord, such as a vii chord) resolving to the tonic I chord, but the PAC is stronger because both chords are in root position (where they are more stable), and the soprano voice ends on scale degree 1. If either the V chord or the I chord are inverted or if the soprano ends on a non-tonic pitch, then the cadence is an IAC.

4.4: Voice Leading with Seventh Chords

There are three main rules we should follow when part writing with seventh chords.

- First, chordal sevenths should almost always be approached by common tone or by step. For example, if you have a chord progression that goes from the tonic chord to the V7 chord, and you are in A Major, you know that you can either approach the chordal seventh (in this case D) from a step up with the C# or a step down with the E.

- All chordal sevenths should resolve by a descending step, to avoid an unresolved seventh, unless you are suspending the chordal seventh, meaning that you are keeping it the same note for the next chord, or you are writing a I-V4/3-I6 chord progression

- Sometimes, you can omit a voice in a root position, dominant seventh chord, if it helps with voice leading. The only voice that you are allowed to omit is the fifth. If you do this, the root should be doubled.

4.5 Voice Leading with Seventh Chords in Inversions

Leading-tone seventh chords, the ⅶo7 diminished and ⅶø7, have two possible functions:

- To substitute for the Ⅴ or Ⅴ7 chord as part of the dominant, or

- Placed between tonic chords, to prolong the tonic in a stepwise voice leading

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🎵Unit 1 – Music Fundamentals I (Pitch, Major Scales and Key Signatures, Rhythm, Meter, and Expressive Elements)

🎶Unit 2 – Music Fundamentals II (Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture)

🎻Unit 3 – Music Fundamentals III (Triads and Seventh Chords)

🎹Unit 4 – Harmony and Voice Leading I (Chord Function, Cadence, and Phrase)

🎸Unit 5: Harmony and Voice Leading II: Chord Progressions and Predominant Function

🎺Unit 6 – Harmony and Voice Leading III (Embellishments, Motives, and Melodic Devices)

🎤Unit 7 – Harmony and Voice Leading IV (Secondary Function)

🎷Unit 8 – Modes & Form

🧐Exam Skills

📚Study Tools

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.