Cesar Torruella

AP Music Theory 🎶

72 resourcesSee Units

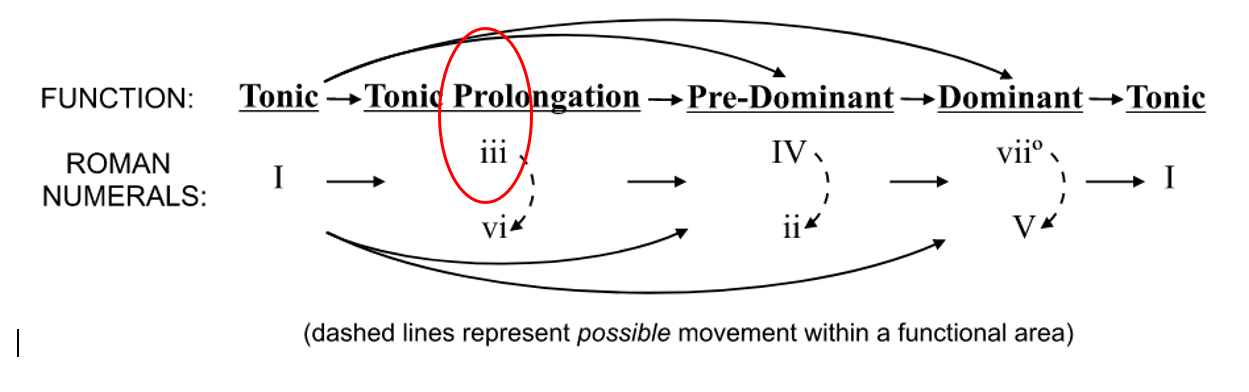

As a quick refresher, here are the functions of all of the diatonic chords we have learned so far, and how we can use them in a progression. Remember, we usually use the supertonic and the subdominant chords as predominant chords, the dominant and leading tone chords as dominant function chords, and the submediant as a weak predominant or a tonic prolongation chord. The tonic chord, of course, has a tonic function, and it is our “home” chord where we go when we want stability in the chord progression.

There is only one more diatonic chord to learn: the mediant chord.

Harmonic flowchart in Major Key: iii as tonic prolongation. Image from Robert Hutchinson: http://musictheory.pugetsound.edu/mt21c/HarmonicFunction.html

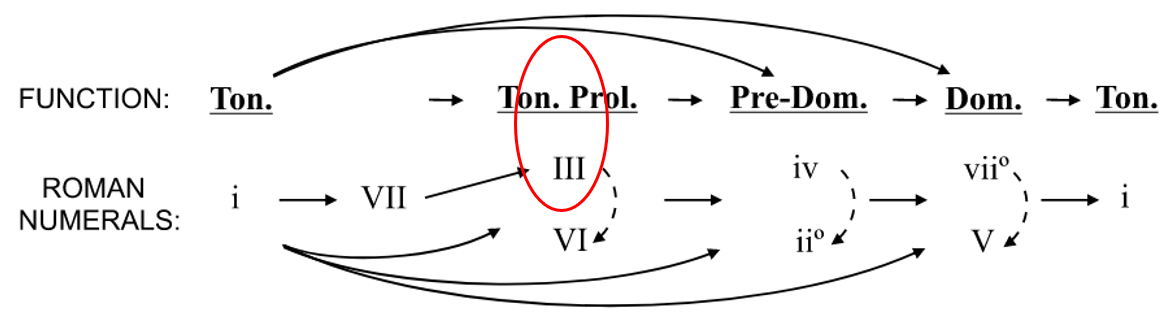

Image from Robert Hutchinson: http://musictheory.pugetsound.edu/mt21c/HarmonicFunction.html

A name is assigned to each scale degree. Tonic, Supertonic, Mediant, Subdominant, Dominant, Submediant, and Leading Tone. The Mediant degree refers to degree 3 of any Major Scale.

The iii or III chord serves as a very weak predominant chord, or as a prolongation of the tonic. Some textbooks call this an expansion of the tonic as well, especially if it appears at the beginning of a phrase (I-iii or i-III.).

We are using Roman Numerals to identify and analyze music. On Unit 3 we went over the harmonic functions and names for each harmony and each scale degree

The mediant triad or iii (III in Major) is rarely used in harmonic progressions of 18th-century style, also called common practice. However, when it does come up, it is usually as a very weak predominant or as an expansion of the tonic. Let’s explore both of these options.

The Mediant as a Weak Predominant

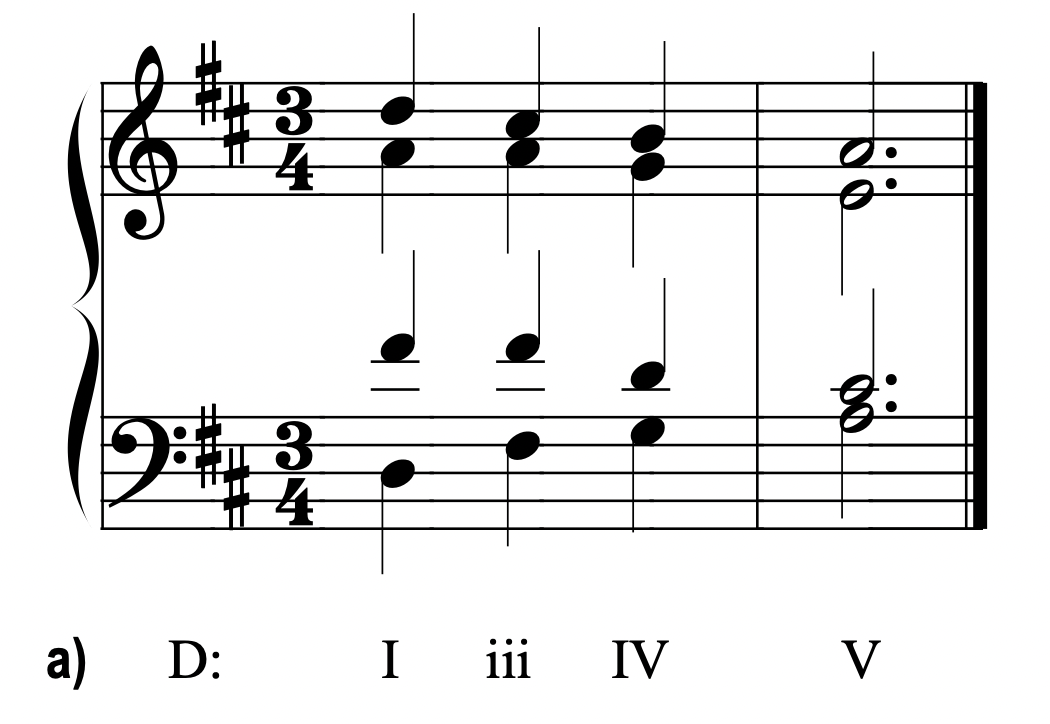

First, we can consider the mediant as a very weak predominant in contexts when it is followed by a predominant section with stronger predominant chords. For example, a I-iii-IV progression is common when it comes to the mediant chord. It would also be acceptable to have a ii or iio chord following the mediant. If this is the case, the supertonic is almost always in first inversion with the third doubled, so as to strengthen the subdominant tones in the supertonic chord.

If the iii chord and the vi chord are both used in a harmonic progression, then the iii chord will almost always come before the vi chord, as the vi chord is considered a stronger predominant chord than the iii chord. For example, if you are in a minor key, you might have a i-III-VI-iio progression for your tonic and predominant section.

Here is an example:

Image via https://myweb.fsu.edu/nrogers/Handouts/iii.pdf

The Mediant as a Dominant Chord

Since the mediant is not a very strong chord, you will almost never see it functioning as a predominant alone – if you are seeing a I-iii-V progression, then you might want to double check your analysis. However, there is one place where this might happen: when the mediant chord is functioning as a dominant chord!

Wait a second… we just said that the mediant was the weakest chord in a harmonic chord progression, and it can barely even be considered a predominant chord. How did it suddenly become a dominant chord?

In first inversion, the mediant chord has the fifth, seventh, and third scale degrees of a diatonic scale. The dominant chord, on the other hand, has the fifth, seventh, and second scale degrees. So, in first inversion, the mediant chord sounds very much like a dominant chord with a non-chord tone.

Therefore, a iii6-V progression probably means that the iii chord is not really a mediant chord – it’s just a dominant chord with a non-chord tone, where the third scale degree resolves down to the second scale degree.

This is also where you might see a III+ chord come up in minor key. Usually, in minor key, we don’t raise the leading tone when spelling the mediant chord, because it gives us a ugly, dissonant augmented chord. However, if there is a III+-V progression, you can assume that once again, the mediant chord is functioning as a dominant chord, which is why the leading tone is raised.

There is no special way to notate this in AP Music Theory – if you see it come up, just write III+6-V or iii6-V. However, if you have to perform a contextual analysis, you can note that the III chord has a dominant function.

Expanding the Tonic With the Mediant

How do we expand the tonic with the mediant? You can always just write a I-iii-I or a i-III-i chord progression in the tonic section of a phrase. Remember to use proper voice leading for this: it might be more practical to write a I-iii-I6 chord so you can keep the mediant in the bass line: this also helps us move away from the very stable tonic in root position. Adding more instability with the inverted tonic chor will allow for a smoother transition into the predominant section of the phrase.

The more common way to use the mediant chord to expand the tonic, however, is to insert a non-functional IV chord after the iii chord. Why do we say the IV chord is non-functional? It’s not that it isn’t used to make the harmony more interesting. Instea, it is non-functional as a subdominant chord, meaning that we are not meant to hear a strong IV-I cadence in the progression. Often, we might write a IV-I6 progression to weaken the cadence.

When writing a I-iii-IV-I tonic expansion, we usually want to write a melody that moves down in steps. This is especially effective if you can put the melody on the soprano line. For example, doubling the root in the I chord will give you the 8th scale degree in the soprano line. Then, move down to the 7th scale degree, which is the fifth of the iii chord. The 6th scale degree will be the third of the IV chord. And, finally, the fifth scale degree will be the fifth of the I chord. The 8=7=6=5 melody will not only sound good, but it will also help listeners hear the tonic all the way through the tonic expansion, since we start on the tonic in the melody, and move stepwise down until we reach another tonic chord. Everything else just sounds like a passing tone with underlying harmonies.

Remember that you should double the root of the chord in each chord – especially the mediant chord, which is already quite a weak chord. However, in the IV chord, there is some leeway to double the third because we don’t want to emphasize the subdominant function of the IV chord.

We should write the iii and the IV chords in root position. However, the tonic chords might be in first inversion. It is especially common to see a tonic chord in first inversion at the end of this tonic expansion, as in a I-iii-IV-I6 progression.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: Can you write a harmonic chord progression in a T-PD-D-T phrase using all seven diatonic chords? Remember the rules for which tonic expansion and which predominant chords come first! (hint: you don’t have to use all the diatonic chords in terms of their “usual” function – if you’re using the V chord as the dominant, what else can the vii chord be used for?)

The Mediant in Minor Keys: Tonicization and Modulation

When we are writing in minor key, the mediant III chord is the tonic chord of the relative major of that minor key. For example, if we are in b minor, then the III chord will be D Major, which is the relative major of b minor.

Why is this useful information? Sometimes, in order to add harmonic interest to a piece, composers want to transition to other keys. When composers only borrow a few chords from a different key for a short harmonic progression in another key, then we call that tonicization. When composers stay in the other key for a longer section of the piece, such that we perceive that new key as our ‘home’ key, we call it modulation.

Often, when writing pieces in minor, composers want to modulate to the relative major key. This is especially common when writing sonatas. A movement of a sonata usually has three sections: a theme, a development, and a recap of the theme. Of course, there are several variations on this structure, and not all movements of all sonatas have this structure. However, the structure itself is called sonata form. If the sonata is written in minor key, then a composer will often try to modulate to the relative major in the development section.

If you are analyzing a piece of music in minor key, and you suddenly see a lot of IIIs, VIIs, and VIs, you might have found a modulation, where the section is written in the relative major key. Here, the IIIs are functioning as the major tonic, the VIIs are functioning as the major dominant, and VIs are functioning as the major subdominant.

In order to understand this better, let’s pretend that you are in d minor. The tonic is a d minor triad, and the dominant is an A major triad, with the C# (the leading tone) raised. Now, suppose you start seeing a lot of C naturals, and there are a lot of F major chords and C natural major chords. There are also a lot of Bb major chords.

Well, this is odd, you might think. We usually don’t see VII-III progressions or VI-VII progressions. However, let’s just look at the notes. A VII-III progression in d minor is just a C-F progression, which is a V-I progression in F Major. And, a Bb-C progression would be a IV-V progression in F Major. So, it is likely that the composer has modulated to F Major. If this is the case, you should analyze the chord progressions and harmonies in F Major, until you start to see the piece transition back to d minor.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🎵Unit 1 – Music Fundamentals I (Pitch, Major Scales and Key Signatures, Rhythm, Meter, and Expressive Elements)

🎶Unit 2 – Music Fundamentals II (Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture)

🎻Unit 3 – Music Fundamentals III (Triads and Seventh Chords)

🎹Unit 4 – Harmony and Voice Leading I (Chord Function, Cadence, and Phrase)

🎸Unit 5: Harmony and Voice Leading II: Chord Progressions and Predominant Function

🎺Unit 6 – Harmony and Voice Leading III (Embellishments, Motives, and Melodic Devices)

🎤Unit 7 – Harmony and Voice Leading IV (Secondary Function)

🎷Unit 8 – Modes & Form

🧐Exam Skills

📚Study Tools

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.