Sitara H

Law 💼

8 resourcesSee Units

Establishing Women's Right to Vote 📜

Overview

- Congress ratified ✅ the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution on August 18th, 1920.

- It declared that no US citizen could be denied their voting rights based on sex, effectively granting women suffrage or the right to vote.

The Women’s Suffrage Movement 🗳️

Seneca Falls Convention

The origins of the female suffrage movement can be traced back to the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, which was the first woman's rights convention ever to be held in America. At this point in the movement, however, the focus wasn't exclusively on gaining suffrage but rather on generally discussing the conditions of women and how to improve their social and political standing. One hundred of the delegates present signed 📝 a Declaration of Sentiments, modeled after the Declaration of Independence, declaring that women were citizens and equal to men.

The first organizations, explicitly created with the eventual goal of women's suffrage, were established in 1869. There were 2️⃣main activist groups: Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), while Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and Henry Blackwell founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

The key 🗝️ difference between these two rival groups was their position on the Fifteenth Amendment, which made African American men citizens and granted them suffrage. AWSA was in support of it, while NWSA opposed the Amendment because it excluded women.

In 1890, both organizations merged into NAWSA, or the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

The Fight for Suffrage ⚔️

In the 1870s, suffragists (women's suffrage activists) began trying to draw attention to the movement through more drastic measures. Many would attempt to vote at polling places, then file lawsuits when rejected - Susan B. Anthony was even arrested 👮 and put on trial for attempting to vote "fraudulently" in the presidential election of 1872. Suffragists were trying to take a lawsuit to the Supreme Court, hoping that the justices would declare that women were entitled to vote according to the Constitution.

In 1875, however, the Supreme Court ruled through Minor v. Happersett that the right to vote wasn't granted to anyone in the Constitution, essentially rejecting women's suffrage.

Alternative Methods ♻️

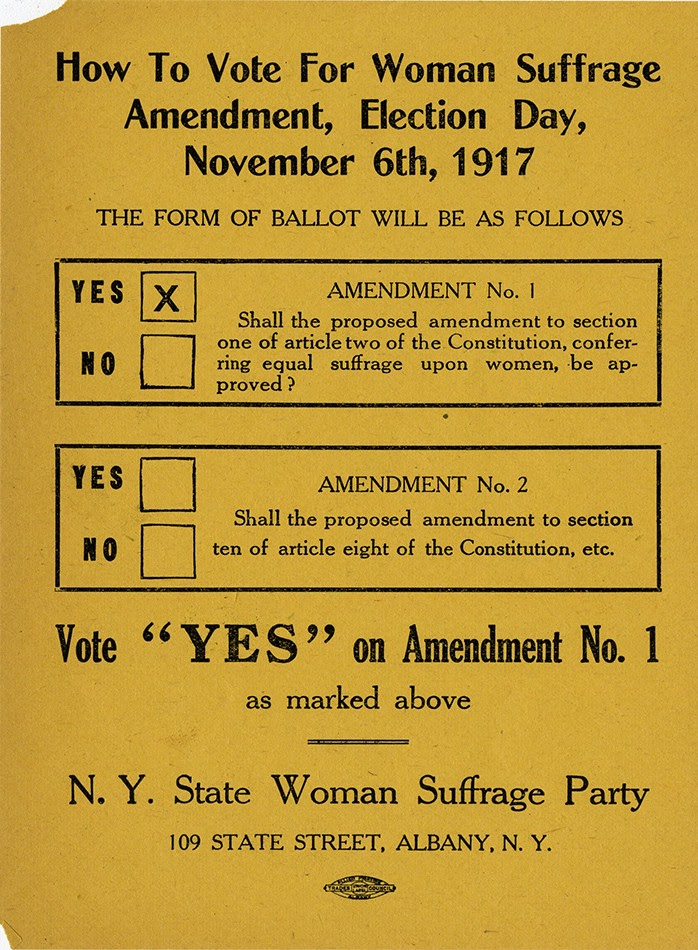

Thus, suffragists had to resort to other ways to further their cause, specifically at the state level. NAWSA shifted its focus to achieving victories at the state level-- they hoped that if enough states granted the women the right to vote, then federal legislation doing so would soon follow.

Over half of all states had granted women voting rights by the time the 19th Amendment was ratified.

Famous Suffragists 👩⚖️

Susan B. Anthony

Before women's suffrage, she was a fervent abolitionist and advocate for prohibition. She spent many years campaigning to expand married women's property rights and turned her focus towards suffrage because she concluded that it would force the government to keep women's interests in mind. She was NAWSA's second president.

Alice Paul

She was determined to win the vote by any means necessary and encouraged various civil disobedience tactics such as parades, marches, and protests. However, her methods frustrated the more conservative wing of NAWSA, and in 1914 Paul left the group to form the Congressional Union (later the National Woman's Party). The group's most outrageous action was a seven-month picket in front of the White House, which got many of its leaders arrested but drew public sympathy towards the cause. In 1920, Paul first proposed an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution, granting both men and women equal rights on a national level-- Congress has not yet ratified it.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

An activist for many progressive causes throughout her life, she helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention with many other reformers. After her fight against the 15th Amendment, because it excluded women, she continued to push for women's political equality-- she advocated for the reform of marriage/divorce laws, expanding education for girls, and even campaigned against the oppression of women in the name of religion.

Lucy Stone

While Stone was a famous abolitionist and suffragist in her own right, she is perhaps most famous for refusing to change her last name when she married abolitionist Henry Blackwell in 1855, citing that the tradition refused to recognize women as independent beings. Unlike Stanton and Anthony, Stone supported the 15th Amendment and helped found AWSA, which fought for woman suffrage on the state level. She also began publishing The Woman's Journal in 1871, a weekly feminist newspaper.

Ida B. Wells

A famous anti-lynching activist, she later shifted her focus to organizing on behalf of many civil rights causes, including women suffrage. However, she faced significant opposition in particular due to many white suffragists not wanting to march along with black people. Wells pushed forward regardless, but her experiences showed that Black people still faced setbacks even after the US abolished slavery.

Opposition to Women’s Suffrage 🪧

Some parts of American society strongly opposed ❌ the suffrage movement, despite its generally well-organized methods of attracting attention.

Specifically, brewers and distillers were opposed to female enfranchisement-- they assumed that women would generally vote for prohibition 🍷 (the outlawing of alcohol), hurting their business. Many businesses were also in favor of restricting the right to vote for women because they feared women would vote to eliminate child labor 🧒, forcing them to pay a higher wage to the adult laborers they would have to hire instead.

Many women, especially those of upper-class families, were also opposed to granting women suffrage. They argued that politics was a "dirty business" and that getting involved politically would be beneath a woman's uprightness.

Connect with other students studying law with Hours 🤝

Browse Study Guides By Unit

👨⚖️Landmark Cases

📜The Amendments

📜Bill of Rights

The 1st Amendment

- Establishing a Universal Right to Vote Under the 15th Amendment

- What Led Up to the Passing of the Amendment? 👍

- What Happened After the Passing of the 15th Amendment? How Did it Affect the US? ⚖

- Tying into the Civil Rights Movement… 🎀

- Wrapping Up: Voting Rights = Super Important! 🤩

- Establishing Women's Right to Vote 📜

- Overview

- The Women’s Suffrage Movement 🗳️

- Famous Suffragists 👩⚖️

- Opposition to Women’s Suffrage 🪧

- The 5 basic rights established by the 1st Amendment

- Bill of Rights 📝

- Free Exercise of Religion 🙏

- Broad Interpretation 🌎

- Narrow Interpretation 🏠

- Literal Interpretation 🧍

- Employment Division v. Smith (1990) 💼

- Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (1993) 🐻

- Free Expression 💬

- Freedom to Assemble, Petition, and Associate ⚠️

- ...and That's a Wrap! 🌮

Fiveable

Resources

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.