J

Jeanne Stansak

dylan_black_2025

AP Microeconomics 🤑

95 resourcesSee Units

What is Monopolistic Competition?

Monopolistic competition is an imperfect market structure where many, various sized firms compete for market demand shares. This type of market structure has some characteristics that are the same or similar to perfect competition, as well as some characteristics that are the same or similar to monopolies. Some examples of monopolistic competition include fast-food restaurants, clothing companies, jewelers, hair salons, and furniture stores.

Characteristics of Monopolistic Competition

- Many, various sized firms - unlike monopoly, a monopolistically competitive market has many firms

- Firms are "price makers" - each of these firms have a degree of market power, so they are price makers

- Low barriers to entry (i.e. means that firms can enter/leave easily) - like perfect competition, monopolistically competitive markets are easy to enter and leave

- Firms break even in the long-run - as we'll see in more detail, in the long run, there is an adjustment in the market from which the market equilibrates to normal profits

- Products sold are differentiated - each firm will sell a related, but different product. For example, every fast food restaurant sells the same general type of product (food, but fast!) but may have different products specifically (I don't get tacos at Burger King)

- Non-price competition is used - because firms are differentiated, they can use non-price competition, such as advertising, to signal substitutes to other businesses (them!) to consumers

- Firms are inefficient when left unregulated - like a monopoly, there will be deadweight loss both in the short run and long run because of...

- Firms experience "excess capacity" in the long-run - these markets are productively inefficient! They do not produce where price = min ATC

Characteristics Compared to Other Market Structures

As stated earlier, the market structure of monopolistic competition has characteristics that are like perfect competition, but also like monopolies. The chart below details which characteristics are similar to the other market structures.

| Perfect Competition | Monopoly |

| Many Firms | Market power / firms are "price makers" |

| Low Barriers | Demand > MR |

| Firms Compete | Non-price competition |

| Firms break even in the long-run | Both allocatively and productively inefficient |

Non-Price Competition

Monopolistic competition uses brand names and packaging as a type of non-price competition. The firms use this in order to stand out and be easily recognizable and distinguishable from their competitors. Think about Chick-fil-A; they are known for their customer service, making them different from other fast-food restaurants.

Another example is Nike's signature swoosh logo, which can be recognized all around the world. Nike also uses product attributes and services as non-price competition. This helps them distinguish how their products are different from the others in the market. They may show how their shoes' soles provide consumers with more speed than other brands, thus enticing consumers to purchase their product.

The final method used for non-price competition is advertising. Monopolistically competitive firms use advertising to generate demand for their product and to make consumer demand more elastic, meaning consumers will become more willing to switch from one product to another.

Graphing Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic competitors can earn positive, negative, or zero economic profit in the short run, and they will break even in the long run (i.e. earn a normal profit) because of low barriers to entry/exit. The graph for a monopolistically competitive firm is very similar to a monopoly, and many people think they look almost identical. The main difference in the elasticity of the demand curve. The demand curve is more elastic in monopolistic competition than it is in a monopoly mainly because there are many more firms in monopolistic competition. However, in essence, a short run monopolistically competitive firm will look the same (in theory) to a monopoly.

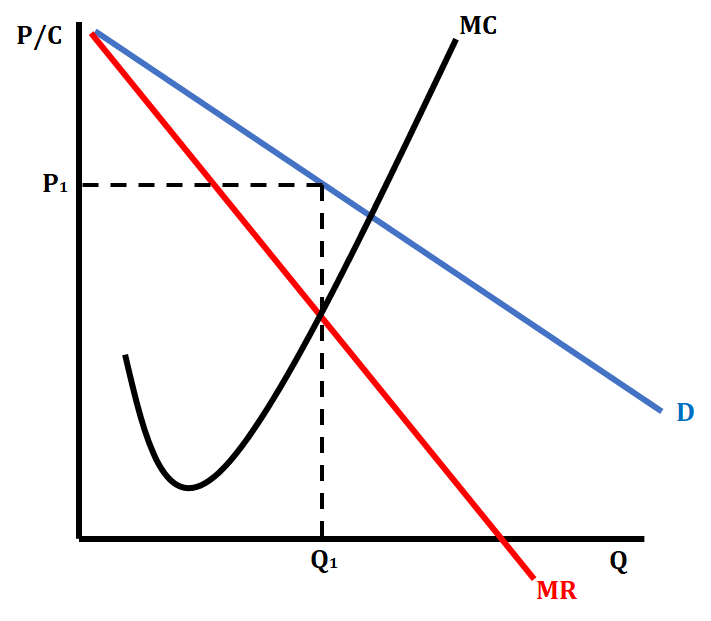

You can see in the graph below that both the demand (D) and marginal revenue (MR) curves are more elastic. We still identify profit-maximizing output and price the same way in monopolistic competition as we do in a monopoly. We identify output where MR=MC, and then go up to the demand curve and over to find the price. This graph is missing ATC, but that could be drawn anywhere as long as it follows the traditional shape of the ATC curve and hits a minimum where ATC = MC.

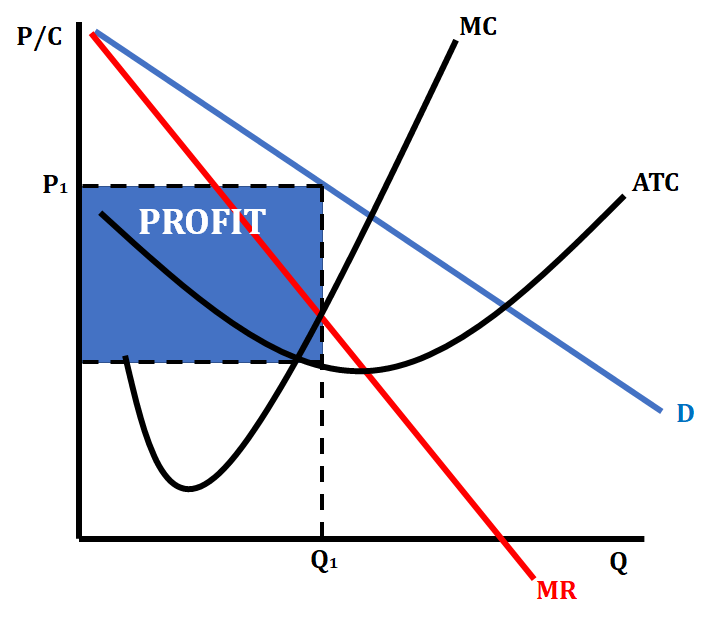

Monopolistic Competition Earning a Profit

When a monopolistically competitive firm is earning a profit, the average total cost (ATC) will be located below the price on the graph. The section between the price and ATC make up the profit area.

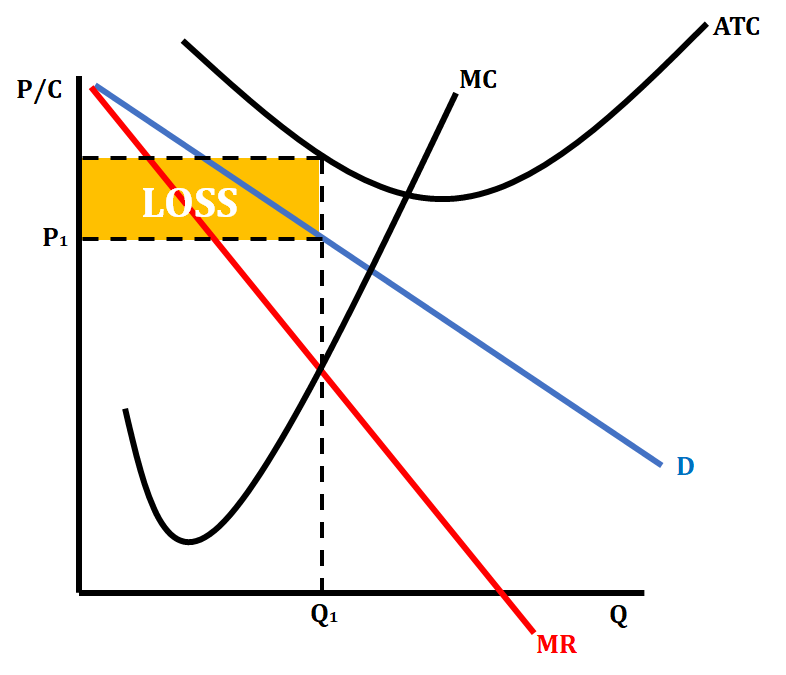

Monopolistic Competition Earning a Loss

When a monopolistically competitive firm is earning a loss, the average total cost curve will be located above the price on the graph. The section between the price and ATC is labeled as the amount of the loss.

Monopolistic Competition in the Long-Run

When a monopolistically competitive firm is in the long-run, the economies of scale portion of the ATC curve will be tangent to the demand curve at the profit-maximizing price level. When drawing this graph, it is very important to make sure it is tangent in the economies of scale (downward-sloping) region because we do not want to indicate that the firm is productively efficient by having it tangent at minimum ATC.

Going from Short Run to Long Run

When monopolistic firms earn a profit in the short run, it compels firms to enter which provides more close substitutes and less market share for the existing firms. This leads to the demand and MR curves shifting left together so that the demand curve becomes tangent with ATC.

When monopolistic firms earn a loss in the short run, it compels firms to exit which provides less close substitutes and more market share for the existing firms. This leads to the demand and MR curves shifting right together so that the demand curve becomes tangent with ATC.

You may think this looks really messy and confusing, but it's actually all things you've learned! All that's happening is the same thing you learned about in perfect competition. Firms respond to profits/loss by entering or leaving the market. This shifts demand and MR just like how MR = D = AR = P shifted up or down in perfect competition.

Excess Capacity

Excess capacity is the difference between a firm's current inefficient level of production and the productively efficient level of output. In the long run, a perfectly competitive market is both allocatively inefficient (P != MC) and productively inefficient (P != min ATC). When we are productively efficient, we have no excess capacity.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

💸Unit 1 – Basic Economic Concepts

📈Unit 2 – Supply & Demand

🏋🏼♀️Unit 3 – Production, Cost, & the Perfect Competition Model

⛹🏼♀️Unit 4 – Imperfect Competition

💰Unit 5 – Factor Markets

🏛Unit 6 – Market Failure & the Role of Government

🤔Exam Skills

📚Study Tools

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.