Dalia Savy

Haseung Jun

A

Audrey Damon-Wynne

AP Psychology 🧠

334 resourcesSee Units

Principles of Sensation

Sensation is the process where our sensory receptors and brain interpret the stimulus energies around us from our environments. We are able to process information in two different ways:

- ⬆️Bottom-up Processing: This processing starts at the sensory receptors and works up to the brain, most of the information associated with bottom-up processing has to do with your five senses: sight 👁️, hearing 👂, smell 👃, taste 👅, and touch ✋.

- For example, we detect the lines, angles, and colors that form a flower 🌼 🌸

- Think: What am I looking at?

- ⬇️Top-down Processing: This processing constructs perception, your organization of sensory information, from the sensory input collected by drawing on experiences and expectations.

- Basically, it's when you interpret what your senses detect.

- You use your memories, history, and emotion to interpret different events.

- Think: Is that something I’ve seen before?

Sensation is like feeling your socks when you put them on. But after a while, you tend to forget about those socks and not feel them, right? That's because of a combination of sensory adaptation and sensory habituation. Sensory adaptation refers to the situation when you have decreasing responses to a stimuli due to constant stimulation. Sensory habituation refers to your perception of sensation depending on how much you focus on them. Your sensation is dependent on your senses, but it can also be dependent on perception.

Your sensation can be thought as the physical senses. But we also have senses that help us know our body position. Though you'll learn this in more depth in later chapters, the vestibular and kinesthetic sense helps you with balance and positioning. Vestibular senses tells you where your body is positioned in relation to space, while kinesthetic senses tell you where your specific body parts are positioned and oriented. All these senses are divided into three categories: energy senses, chemical senses, and body position senses.

| Energy Senses | Vision 👀 | Rods, cones (retina) |

| Hearing 👂 | Cochlea | |

| Touch 🤏 | Pain, pressure, texture, temperature (skin) | |

| Chemical Senses | Taste (gustation) 👅 | sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami (taste buds) |

| Smell (olfaction) 👃 | smell receptors | |

| Body Position Senses | Vestibular sense 🤸♂️ | Hairlike cells located in semicircular canals (inner ear canal) |

| Kinesthetic sense 🙋♀️ | Receptors in muscle and joints |

Gestalt Principles

How do psychologists study our interpretation of sensory information? In the 1900s, a group of psychologists noticed that we tend to organize our cluster of sensations into a gestalt, or a whole/form. These Gestalt psychologists have identified a number of principles that explain how we do this.

In the image below, you may see eight black circles with white lines intersecting them. That is the actual visual stimuli (sensation). However, you may also see a cube, although there isn't actually one there. This is your mind working to create a perception that is actually an illusion called the Necker cube, named after a Swiss dude who first published it in 1832. It's a great example of the idea that "the whole can be greater than the sum of its parts."

Image Courtesy of Wikiwand.

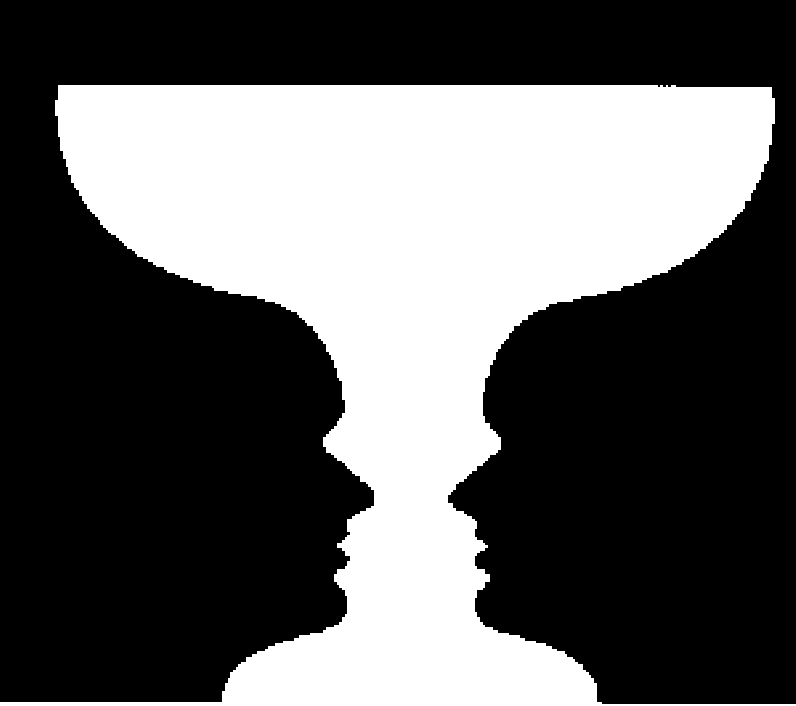

Another aspect of perception that Gestalt psychologists studied is the figure-ground relationship. This principle explains how we can distinguish a subject from its background. If you look at the image below and consider the black as the background, you will see a white chalice, or vase, as the figure. If you look at the image with the white as the background, you will see two black faces looking at each other. Our ability to view either one of these objects demonstrates the figure-ground relationship.

Image Courtesy of Research Gate.

We also tend to group different stimuli together. We may group nearby objects together (proximity), perceive continuous patterns rather than discontinuous ones (continuity), and fill in gaps to form a whole object (closure). Consider the example of grouping below:

DEMON DAY BREAK FAST. You probably read this as Demon, Day, Break, and Fast, but these words can also be grouped into Monday, daybreak, or breakfast.

Interpreting Sensory Information

To process sensory information, our sensory systems convert one form of energy into another form of energy. This is done through sensory transduction. With all of our five senses, we:

- Receive the sensory information

- Transform it into neural impulses, and

- Deliver the information to our brain to be further interpreted 🧠

Philosopher Gustav Fechner studied our awareness of faint stimuli and coined the term absolute threshold. This is the minimum stimulation needed to detect any stimuli 50% of the time. In basic terms, the absolute threshold is the lowest level of stimulus needed to detect a smell, a sound, or a ray of light. Stimuli that are below your absolute threshold are considered subliminal because they are there but you're not consciously aware of them.

Image Courtesy of Tufts.

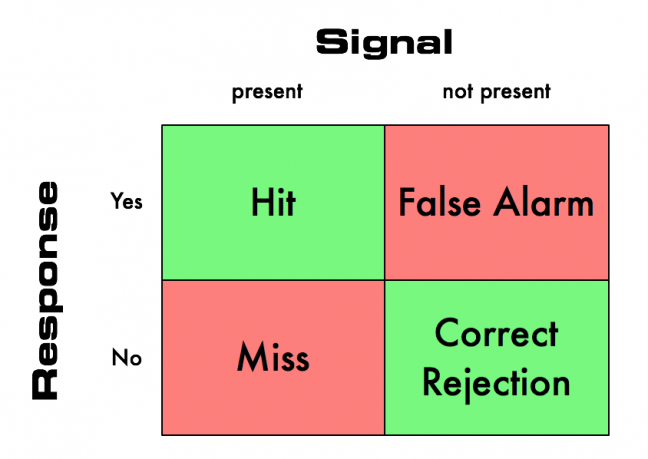

Detecting a faint stimulus also depends on our psychological state, which has to do with the signal detection theory. This theory predicts when we detect a faint stimulus in our surroundings, being the signal, among all background stimuli, being the “noise.” These theorists seek to understand why we respond differently to the same stimuli, and ultimately pertained it to our experiences and expectations.

Along with detecting faint stimuli, how do we detect the differences between really similar stimuli? For example, how can a musician hear when their instrument is untuned? 🎻🎹 We can attribute this detection to the difference threshold, or the just noticeable difference. This is the minimum difference between two stimuli required for detection 50% of the time. For example, we may not feel a significant difference between a 61-pound weight and a 62-pound weight. However, we would feel a significant difference between a 50 lb weight and a 100 lb weight.

Ernst Weber noted Weber’s Law which states that to perceive a difference, two stimuli must differ by a constant amount.

When a stimulus is unchanging, you eventually become less sensitive to it. This is known as sensory adaptation where our nerve cells fire less frequently. An example of sensory adaptation is when you walk outside, you might smell the fresh smell of grass, right? Eventually, though, the smell just disappears and you no longer smell grass even though you are outside. This is because you adapted to the scent and are no longer aware of it. Sensory adaptation allows us to focus on changes in our surroundings amongst background “noise.”

Practice Question

The following question is from the Advanced Placement Youtube Channel. All credit given to them.

- Melly just moved into her first apartment. She is excited to decorate her apartment and make it her own. Her first step is choosing paint colors for the walls. She has a hard time choosing between two different shades of blue. Melly has little money for furnishings and ended up with a lumpy chair from her mother and a sofa that was covered in slightly itchy fabric. On her first evening in the apartment, she looked out her window and realized that the park was a lot further away than she had thought. Still, when she looked at her apartment, she didn't see any flaws, she saw a home. Based on the scenario described, how is Melly using each of the following concepts to help her settle into her new apartment?

- Sensory adaptation

- Difference Threshold

- Top-Down processing

Remember, when you answer FRQs, you should keep CHUG SODAS in your mind. It's one of the many acronyms you could recall during the test to make sure you nail the FRQs.

📝Read: AP Psychology - FRQ Guide (More on CHUG SODAS)

For sample responses, watch this video.

🎥Watch: AP Psychology - Principles of Sensation and Perception

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🔎Unit 1 – Scientific Foundations of Psychology

🧠Unit 2 – Biological Basis of Behavior

👀Unit 3 – Sensation & Perception

📚Unit 4 – Learning

🤔Unit 5 – Cognitive Psychology

👶🏽Unit 6 – Developmental Psychology

🤪Unit 7 – Motivation, Emotion, & Personality

🛋Unit 8 – Clinical Psychology

👫Unit 9 – Social Psychology

🗓️Previous Exam Prep

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.