Dalia Savy

A

Audrey Damon-Wynne

AP Psychology 🧠

334 resourcesSee Units

Perceptual Organization

In earlier study guides, we learned how we are able to convert what we see (lightwaves) into neural impulses and how we detect color and shapes. In other words, how we sense visual stimuli, which is also called bottom-up processing. In this study guide, we will learn how we perceive that visual stimuli or make sense of and interpret the images we see (top-down processing). More specifically, we will learn how we perceive form, depth, and motion.

Form perception

Early in the 20th century, a group of German psychologists discovered that we have a natural tendency to organize our sensations into wholes or what they called gestalts. This means that our brains don't just take information in, but we interpret and actually construct our perceptions. The following are some examples of how we do this when perceiving form.

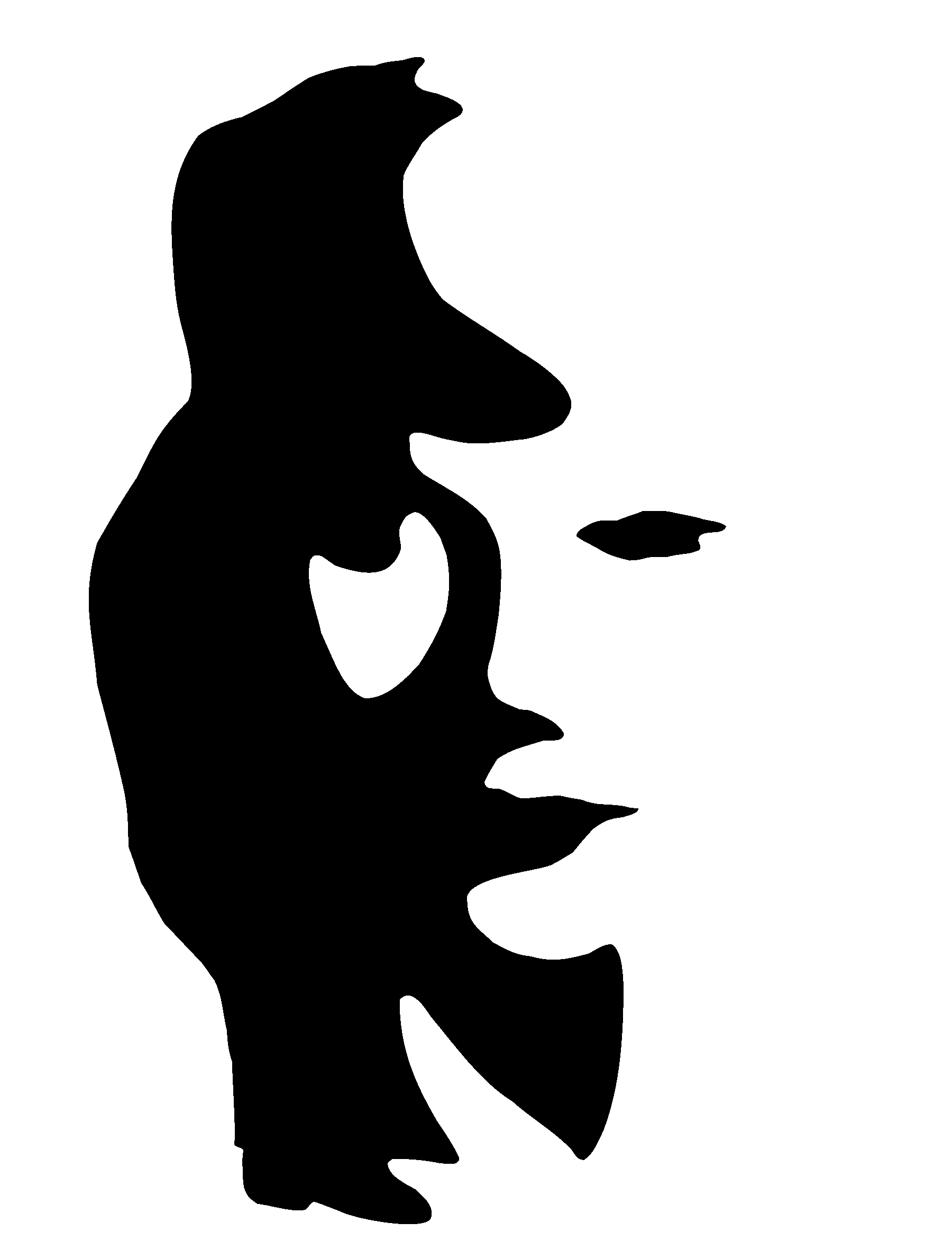

Figure-ground

This is the idea that we naturally organize what we see into objects (figures) that stand out from their backgrounds. For example, in the image below, if you consider the black in the image to be the background, you will see the white as the figure (a woman's face). If you consider the white as the background, you will a saxophone player as the figure.

Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

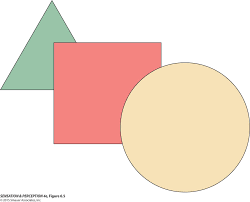

Group Principles

In addition to organizing objects in our visual field into figure and ground, we also naturally organize objects into groups. Some of the most common examples of these principles are:

- similarity: We group similar figures together, for example we perceive a group of baseball players wearing the same color jersey as one team

- proximity: We group nearby figures together, for example, we perceive players sitting together on a bench as one team

- continuity: We perceive smooth, continuous patterns rather than discontinuous ones

- closure: We fill in gaps to create a complete, whole object

- connectedness: We perceive items that are uniform and linked as a single unit

Photo courtesy of Pixabay.

Depth Perception

Depth perception is our ability to perceive objects in 3 dimensions and to judge distance. It also enables us to avoid falling down stairs and off cliffs, as Gibson and Walk demonstrated in their famous study with infants and a make-believe visual cliff (see below). All species, by the time they are mobile, have this ability as it is essential for our survival. In order to perceive depth, we use both monocular (one eye) and binocular (two eyes) cues to perceive depth and judge distance.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons and the National Institute of Health.

👁 Monocular Cues

Monocular cues are available to either eye alone and include:

- Relative Height

- We perceive objects that are higher to be farther away from us. In the image below, it looks like the house is farther away because of this monocular cue.

Image Courtesy of Micky and Marissa.

- Relative Size

- If two images are, in reality, the same size, we would perceive the one closest to us to be larger. For example, if you place one teddy bear close to the camera and another really far away from the camera, the one closer would look larger. This happens even though the two teddy bears are really the same size.

- Interposition

- If one image covers another, it looks closer/larger.

Image Courtesy of Sjsu.

- Relative Motion/Motion Parallax

- When we are in motion, the objects we are looking at look like they are moving, as well. You could see this happening when you're in a car looking out the window.

- Linear Perspective

- Parallel lines look like they come together in the distance.

Image Courtesy of @Psych_Review.

- Light and Shadow

- When there are shadows involved, there is a perception of depth.

Image Courtesy of Jim Foley.

👀 Binocular Cues

Binocular cues depend on the use of both eyes. The main binocular cue is retinal disparity, the difference between the two retinal images that result due to your eyes being about 2.5 inches apart. Your brain judges distance by comparing these images; the greater the disparity (difference), the closer the image is.

Motion Perception

Our ability to perceive motion is important because it allows us to do things like drive, walk and ride a bicycle. Generally, our brains perceive motion by assuming that shrinking objects are moving away and objects that are getting bigger are moving closer. Sometimes, however, we perceive motion when there really isn't any. The phenomenon called stroboscopic movement creates this illusion when we perceive movement in slightly varying images shown in rapid succession. Did you ever create a flip book when you were a kid? That is an example of stroboscopic movement. The same concept applies to film animation; a super fast presentation of Mickey Mouse in slightly different positions will create an illusion of movement.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Another illusion of movement is called the phi phenomenon. This is created when adjacent lights blink on and off in quick succession, like you might see on Christmas lights along the edge of a roof or highway arrows telling us to keep to one side or the other.

Perceptual Constancy

Perceptual constancy is another example of how our brains play tricks on us as we interpret the objects in our visual field. Also called object constancy or constancy phenomenon, it refers to our tendency to see familiar objects as having consistent color, size and shape, regardless of changes in lighting, distance or angle of perspective. In short, our brains interpret stimuli as they are assumed to be, rather than as they actually are.

- Color constancy is perceiving objects as having a consistent color, even as illumination changes. An apple will look red to us outside in the sunlight, and also inside with indoor lighting—despite different light wavelengths reflecting off the apple.

- Brightness constancy, also called lightness constancy, refers to perceiving objects with the same level of brightness, even though the illumination may change. For example, we see snow as white at noon under sunlight and in the evening under moonlight.

- Shape constancy is perceiving objects as having a consistent shape, even as our orientation to it changes. For example, when we look at a refrigerator we see a rectangle. When we open the door, we continue to perceive the door as a rectangle even though technically the image that is being cast on our retina is a trapezoid.

- Size constancy refers to our tendency to perceive objects as unchanging in size, even though our closeness or distance from the object may change.

Perceptual Adaptation

One last concept in the area of visual perception is perceptual adaptation. This refers to our remarkable ability to adjust to changing sensory input. If you wear glasses, you can probably relate to this example. When you get a new prescription, initially you may feel a little dizzy or out of sorts. But after a day or so, everything seems back to normal. A more extreme case of this phenomenon can be experienced when wearing visual distortion goggles that can actually turn your world upside down! But even in this extreme case, people will adjust to this inverted world and even be able to throw a football with some precision.

Courtesy of Dmitry HOH, via Wikimedia Commons.

Practice AP Question

The following question is from the 2011 AP Psychology Exam. It's great review for both this unit and unit 1!

- A researcher designs a study to investigate the effect of feedback on perception of incomplete visual figures. Each participant stares at the center of a screen while the researcher briefly projects incomplete geometric figures one at a time at random positions on the screen. The participant’s task is to identify each incomplete figure. One group of participants receives feedback on the accuracy of their responses. A second group does not. The researcher compares the mean number of figures correctly identified by the two groups.

A. Identify the independent and dependent variables in the study.

B. Identify the role of each of the following psychological terms in the context of the research

- Foveal Vision

- Feature Detectors

- Gestalt principle of closure

C. Describe how each of the following terms relates to the conclusions that can be drawn based on the research.

- Random Assignment

- Statistical Significance

👉Scoring Guidelines for this Question

🎥 Watch: AP Psychology - Visual Anatomy and Perception

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🔎Unit 1 – Scientific Foundations of Psychology

🧠Unit 2 – Biological Basis of Behavior

👀Unit 3 – Sensation & Perception

📚Unit 4 – Learning

🤔Unit 5 – Cognitive Psychology

👶🏽Unit 6 – Developmental Psychology

🤪Unit 7 – Motivation, Emotion, & Personality

🛋Unit 8 – Clinical Psychology

👫Unit 9 – Social Psychology

🗓️Previous Exam Prep

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.