Dalia Savy

Robby May

AP US History 🇺🇸

454 resourcesSee Units

Nixon's Presidency

New Federalism

Under the label of “new federalism,” Nixon shifted responsibility for many social programs from the federal government to state and local authorities. It is often associated with conservative and libertarian ideologies, and advocates for a more limited role for the federal government in areas such as welfare, education, and law enforcement. The idea is to give more autonomy to states and localities to govern themselves and make decisions that best suit the needs of their citizens.

He developed the concept of revenue sharing, by which federal funds (via grants) were dispersed to state, country, and city agencies to meet local needs in the form of block grants. Again, these governments could use the money as they saw fit.

Nixon's Southern Strategy

Nixon devised a political strategy to form a Republican majority by appealing to the millions of voters who had become disaffected by antiwar protests, Black militants, school busing to achieve racial balance, and the excesses of the youth counterculture. Nixon referred to these conservative Americans as the “silent majority.” Many of them were Democrats, including southern whites, northern Catholic blue-collar workers, and recent suburbanites who disagreed with the liberal drift of their party.

To win over the South, Nixon asked the federal courts in that region to delay integration plans and busing orders. He also nominated two Southern conservatives to the Supreme Court. The courts rejected his requests and the Senate refused his nominees.

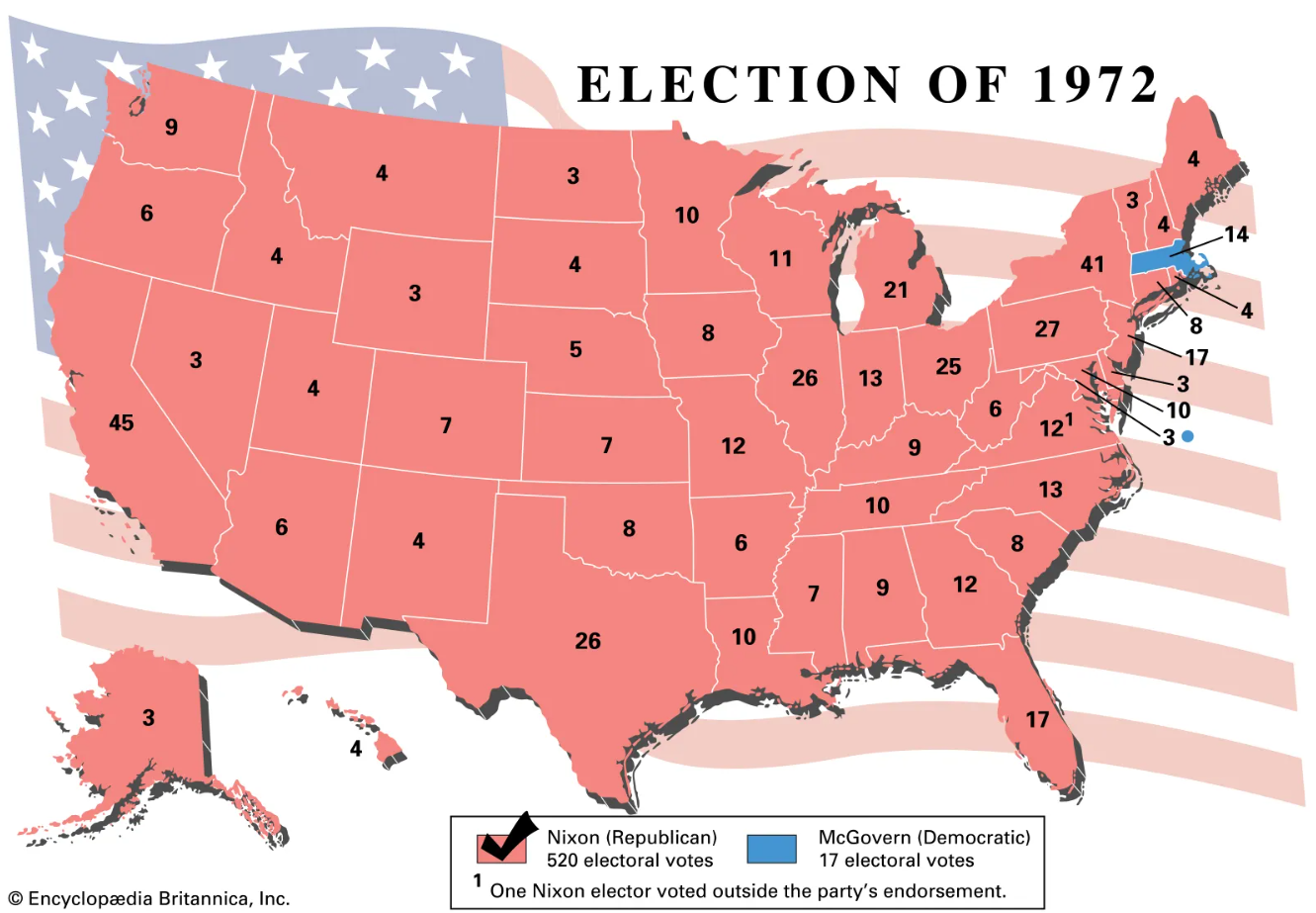

His southern strategy played well with Southern white voters. The success of Nixon’s southern strategy became evident in the presidential election of 1972 when the Republican ticket won majorities in every southern state.

Image Courtesy of Britannica

Roe v. Wade Landmark Case

Roe v. Wade is a landmark case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1973. The case involved a Texas statute that banned abortions, except to save the life of the mother. The Supreme Court struck down the statute, ruling that a woman has a constitutional right to privacy that includes the right to make the decision to have an abortion.

The court's 7-2 ruling held that a state law that banned abortions except to save the life of the mother was unconstitutional. The Court established that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provides a fundamental "right to privacy" that protects a pregnant woman's liberty to choose whether or not to have an abortion.

Distrust in Nixon

War Powers Act

The public discovered that Nixon authorized 3500 secret bombing raids in Cambodia, a neutral country. Congress used the public uproar over this information to attempt to limit the president’s powers over the military.

After a long struggle, Congress passed the War Powers Act over Nixon’s veto in 1973. This law required the president to report to Congress within 48 hours after taking military action. It further provided that Congress would have to approve any military action that lasted more than 60 days. This was also a result of the disastrous Vietnam War.

Image Courtesy of Nixon Library

Watergate Scandal

Nixon was sensitive to the unauthorized release of information about American foreign policy. Anytime leaks occurred, Nixon grew outraged and demanded that they be stopped.

The White House established an informal office of covert surveillance—the “plumbers,” its operatives were called—which began by investigating the national security breaches, but, during the 1972 campaign, branched out into spying on Nixon’s Democratic opponents and engaging in political dirty tricks. They also created an enemies list of prominent Americans who opposed Nixon, the Vietnam War, or both. People on the list were investigated by government agencies, such as the IRS.

Five of the “plumbers” were arrested in June 1972 during a break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office complex in Washington. Nixon personally ordered the cover-up saying, “I want you to stonewall it, let them plead the Fifth Amendment, cover-up, or anything else.”

James McCord, one of the burglars, was the first to break the silence. When he was sentenced to a long jail term, he asked for leniency, informing the judge that he had received money from the White House and had been promised a presidential pardon in return for silence.

By April 1973, Nixon was compelled to fire aide John Dean, who had directed the cover-up but who now refused to become a scapegoat. Two other aids were also forced to resign.

The Senate then appointed a special committee to investigate the unfolding Watergate scandal. The committee’s discovery of the existence of tape recordings of conversations in the Oval Office made regularly since 1970, proved the beginning of the end for Nixon. Nixon tried to invoke executive privilege to withhold the tapes.

Archibald Cox, appointed as Watergate special prosecutor, demanded the release of the tapes, so Nixon fired him. The new prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, continued to press for the tapes. Nixon released only a few of the less damaging ones, but the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in June 1974 in the case United States v. Nixon that the tapes had to be turned over.

By this time, the House Judiciary Committee, acting on evidence compiled by the staff of the Senate committee, had voted three articles of impeachment, charging Nixon with obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress. Faced with the release of tapes that directly implicated him in the cover-up, the president chose to resign on August 9, 1974, and vice president Gerald Ford became president.

Image Courtesy of CBS News

Pardoning Nixon

President Gerald Ford’s presidential honeymoon lasted only a month. On September 8, 1974, he shocked the nation by announcing he had granted Nixon a full and unconditional pardon for all federal crimes he may have committed. Some argued that Ford and Nixon had argued that there had been a secret deal while others argued that it was unfair for him to go free while so many were serving in jail. Ford acted in an effort to end the bitterness over Watergate, but it backfired, eroding public confidence in him and as a result, he would lose the election for his own term.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🌽Unit 1 – Interactions North America, 1491-1607

🦃Unit 2 – Colonial Society, 1607-1754

🔫Unit 3 – Conflict & American Independence, 1754-1800

🐎Unit 4 – American Expansion, 1800-1848

💣Unit 5 – Civil War & Reconstruction, 1848-1877

🚂Unit 6 – Industrialization & the Gilded Age, 1865-1898

🌎Unit 7 – Conflict in the Early 20th Century, 1890-1945

🥶Unit 8 – The Postwar Period & Cold War, 1945-1980

📲Unit 9 – Entering Into the 21st Century, 1980-Present

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

👉🏼Subject Guides

📚AMSCO Notes

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.