Dalia Savy

Robby May

AP US History 🇺🇸

454 resourcesSee Units

Causes of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War, also known as the Second Indochina War, was a conflict that lasted from 1955 to 1975 and was fought primarily in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The causes of the war can be traced back to the end of World War II and the rise of Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. Here is a quick summary of them before getting into the details:

- Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union

- Fear of the spread of communism in Southeast Asia

- U.S. involvement in the First Indochina War (1946-1954)

- The 1954 partition of Vietnam into North and South

- The rise of communist leader Ho Chi Minh in North Vietnam

- The 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident

- U.S. escalation of military involvement in Vietnam under President Lyndon B. Johnson

- The growth of anti-war sentiment and protests in the United States

- The role of the media in shaping public opinion on the war

- Political and economic factors within Vietnam and the region.

Fall of Indochina

After losing their Southeast Asian colony of Indochina to Japanese invaders in World War II, the French made the mistake of trying to retake it. Wanting independence, native Vietnamese and Cambodians resisted. French imperialism had the effect of increasing support for nationalist and Communist leader Ho Chi Minh.

Truman’s government started to give U.S. military aid to the French while China and the Soviet Union aided the Viet Minh guerrillas led by Ho Chi Minh. In 1954, a large French army at Dien Bien Phu was trapped and forced to surrender. After the disastrous defeat, the French tried to convince Eisenhower to send in U.S. troops, but he refused.

Vietnam Divided

By the terms of the Geneva Conference, Vietnam was to be temporarily divided at the 17th parallel until a general election could be held. The new nation remained divided, as two hostile governments took power on either side of the line. In North Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh established a Communist dictatorship. In South Vietnam, a government emerged under Ngo Dinh Diem, whose support came largely from anti-communist, Catholic, and urban Vietnamese, many of whom had fled from Communist rule in the North.

Image Courtesy of Khan Academy

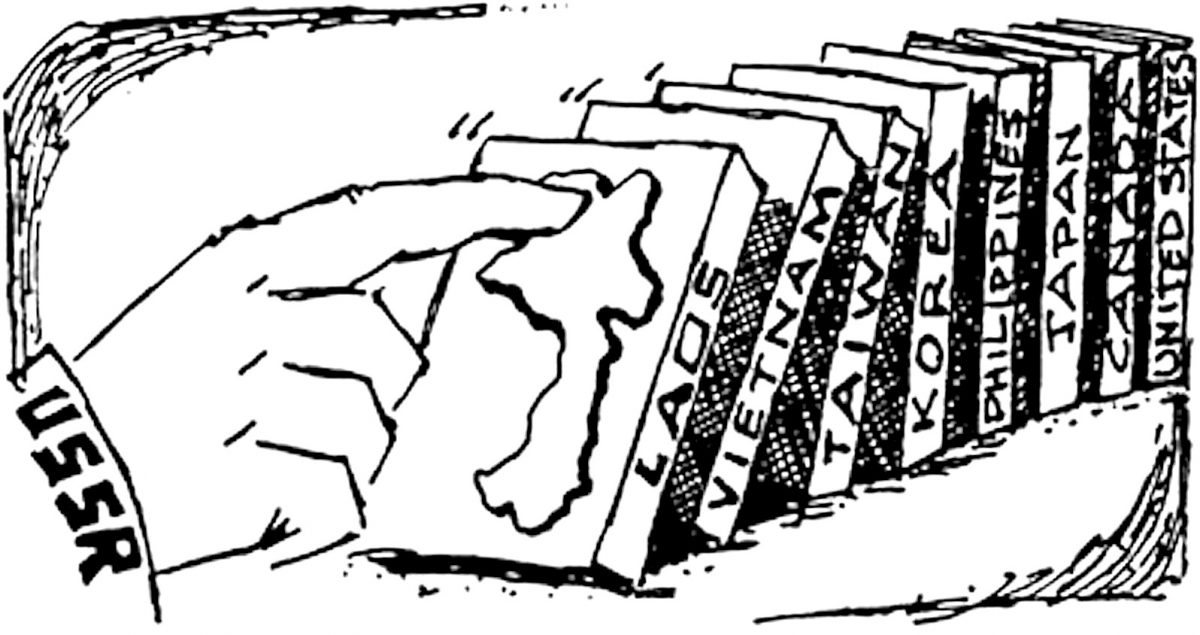

From 1955 to 1961, the US government gave over $1 billion in economic and military aid to South Vietnam in an effort to build a stable, anti-communist state. In justifying this aid, President Eisenhower made an analogy to a row of dominoes. According to his domino theory, if South Vietnam fell under Communist control, one nation after another in Southeast Asia would also fall, until Australia and New Zealand were in dire danger.

Image Courtesy of Political Dictionary

Kennedy Sends Advisors

Kennedy adopted Eisenhower’s domino theory when it came to Southeast Asia. When Kennedy took office, Ho Chin Minh in North Vietnam was directing the efforts of the Vietcong rebels in the South. The war intensified so Kennedy sent two advisors to South Vietnam. They returned pushing for the dispatch of 8000 American combat troops.

The president decided against sending troops but authorized a substantial increase in economic aid to Diem and in the size of the military mission in Saigon. The number of American advisors in Vietnam grew to more than 16,000.

In 1962, Diem failed to win the support of his own people. Buddhist monks set themselves on fire in public protest against him and even Diem’s generals plotted an overthrow. JFK approved a coup that lead to Diem’s overthrow and death on November 1, 1963. The power vacuum in Saigon made further American involvement in Vietnam almost necessary.

Tonkin Gulf Resolution

Lyndon Baines Johnson inherited an American commitment dating to Eisenhower to support an independent South Vietnam. He felt he had little choice but to continue Kennedy’s policy.

On August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the Maddox, an American destroyer engaged in electronic intelligence gathering in the Gulf of Tonkin. They believed that the ship had been involved in a South Vietnamese raid nearby. The Maddox escaped unharmed, but the navy sent another destroyer. On August 4th, the two destroyers responding to sonar and radar contacts opened fire on North Vietnamese gunboats in the area. Johnson ordered retaliatory air strikes on North Vietnamese naval bases.

The next day, LBJ asked Congress to pass a resolution authorizing him to take “all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the US and to prevent further aggression.” Congress voted its approval for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which basically gave the president, as commander in chief, a blank check to take “all necessary measures” to protect U.S. interests in Vietnam. LBJ’s approval in a Gallup poll jumped from 42% to 72%. Until 1968, most Americans supported the effort to contain communism in Southeast Asia.

Escalation of the War

Full-scale American involvement in Vietnam began in 1965 in a series of steps designed to primarily prevent a North Vietnamese victory. Johnson ordered a long-planned aerial bombardment of selected North Vietnamese targets called Operation Rolling Thunder. They were aimed at impeding the communist supply lines and damaging Hanoi’s economy. They proved ineffective.

Johnson authorized the use of American combat troops in South Vietnam. Defense Secretary McNamara recommended sending 100,000 combat troops to Vietnam. He permitted a gradual increase in the bombing of the North and allowed American ground commanders to conduct offensive operations in the South called search and destroy, which only further alienated the peasants. General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, used superior American firepower wantonly, devastating the countryside, causing many civilian casualties, and driving the peasantry into the arms of the guerillas.

These tactics led to the slaughter of innocent civilians. The most notable was the hamlet of My Lai in South Vietnam. An American company led by Lt. William Calley, Jr. killed more than 200 unarmed villagers, mostly women, children, and elderly people, in what was considered a war crime. Westmoreland hoped that he could wage a war of attrition, where communist losses each more would be more than they could recruit to replace them.

The My Lai massacre was a turning point in the American public's perception of the Vietnam War and it is considered one of the most shocking atrocities of the conflict.

Johnson approved the immediate dispatch of 50,000 troops to Vietnam and a future commitment of 50,000 more. By the end of 1967, the United States had over 485,000 troops in Vietnam and 16,000 Americans had already died in the conflict.

Tet Offensive

On the occasion of their Lunar New Year (Tet) in January 1968, the Vietcong launched an all-out surprise attack on almost every provincial capital and American base in South Vietnam. The U.S. military counterattacked and inflicted heavy losses on the Vietcong and recovered the lost territory. The American military victory proved irrelevant to the war the Tet Offensive was interpreted at home.

Image Courtesy of NPR

The destruction viewed by millions of Americans on the TV news appeared as a colossal setback for Johnson’s Vietnam policy. LBJ had been telling the American people that the war was almost over and that the end was almost in-sight. CBS newscaster Walter Cronkite took a quick trip to Saigon to find out what happened. He was horrified by what he saw and exclaimed “What the hell is going on? I thought we were winning the war?” He returned home to tell Americans that it was certain that it was to end in a stalemate.

Johnson’s Announcement

The Joint Chiefs responded to Tet by requesting 200,000 more troops to win the war. By this time, Johnson’s advisors had turned against further escalation of the war. On March 31, 1968, President Johnson went on television and told the American people that he would limit the bombing of North Vietnam and negotiate peace. He then surprised everyone by announcing that he would not run again for president.

Nixon and Vietnamization

When Richard Nixon took office, more than a half-million US troops were in Vietnam. His objective was to find a way to reduce U.S. involvement while at the same time avoiding the appearance of conceding defeat. He said the U.S. was accepting nothing less than “peace with honor”.

Almost immediately, Nixon began the process called “Vietnamization”. He announced that he would gradually withdraw U.S. troops from Vietnam and give the South Vietnamese the money, the weapons, and the training that they needed to take over the full conduct of the war. Under this policy, U.S. troops in South Vietnam went from over 540,000 in 1969 to 30,000 in 1972.

The president proclaimed the Nixon Doctrine, declaring that in the future Asian allies would receive U.S. support, but without the extensive use of U.S. ground forces.

Peace Talks

When the two sides could not reach a deal to end the war, Nixon ordered a massive bombing of North Vietnam (the heaviest air attack of the long war) to force a settlement. After several weeks of B-52 bomber attacks, the North Vietnamese agreed to an armistice, in which the U.S. would withdraw the last of its troops and get back over 500 prisoners of war.

The Paris Accords of 1973 also promised a cease-fire and free elections. In practice, however, the armistice did not end the war between the North and the South and left tens of thousands of enemy troops in South Vietnam. Before the end of the war, the death toll probably numbered more than a million. The armistice allowed the U.S. to extricate itself from a war that claimed over 58,000 American lives. The $118 billion spent on the war began an inflationary cycle that racked the US economy for years.

Fall of Saigon

In April 1975, the US-supported government in Saigon fell to the enemy and Vietnam became a country under the rule of the Communist government in Hanoi. Just before the final collapse, the U.S. was able to evacuate about 150,000 Vietnamese who had supported the U.S. and now faced certain persecution.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🌽Unit 1 – Interactions North America, 1491-1607

🦃Unit 2 – Colonial Society, 1607-1754

🔫Unit 3 – Conflict & American Independence, 1754-1800

🐎Unit 4 – American Expansion, 1800-1848

💣Unit 5 – Civil War & Reconstruction, 1848-1877

🚂Unit 6 – Industrialization & the Gilded Age, 1865-1898

🌎Unit 7 – Conflict in the Early 20th Century, 1890-1945

🥶Unit 8 – The Postwar Period & Cold War, 1945-1980

📲Unit 9 – Entering Into the 21st Century, 1980-Present

📚Study Tools

🤔Exam Skills

👉🏼Subject Guides

📚AMSCO Notes

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.